**Before you check out this article, I would highly recommend downloading the FREE Explosive Speed Package here where you will get instant access to even more content and hockey workouts to make you a faster skater that is not available here.

“How Can I Skate Faster?”

This is the most common hockey training question we get on all of our media platforms.

In this 2-part hockey training series, I will be addressing the main glaring issues hockey players have that are limiting their skating speed and stopping them from performing at their absolute best out on the ice.

These issues are so common among hockey athletes that addressing them can be considered “principles” of hockey program design.

These are the main limiting factors to many hockey players performance, and correcting them has a massive carryover to performance enhancement out on the ice – including skating faster, being more explosive and becoming an all around quicker athlete during games.

I will show you exactly how you can fix these issues, which will allow you to take your game to the next level.

How Can I Skate Faster?

The first issue in this two-part series will be covering the common structural imbalances.

Fixing these structural imbalances will help you skate faster right away, without any on-ice drills. Not only will you be quicker on the ice, your overall power, explosiveness, and performance will improve as well. An imbalanced machine will never function as well as a balanced machine.

Let’s talk first about what I mean when I am talking about “structural imbalances”

Structural imbalances, from a skeletal muscle perspective, can be found in the muscles through structural balance testing. Certain movements during testing and how the athlete moves or how much weight he/she is able to use exposes structural differences and/or compensations.

Ideally, the perfect athlete should be structurally balanced from the upper body to the lower body, and from the left side to the right side.

Depending on which tests you use; front squats, body weight squats, push ups, range-of-motion tests, single leg hopping, step ups, external rotation with dumbbells, and simply just assessing how they carry themselves and how they move can all tell you something about what is going on structurally.

There are many more tests than the movement screens I listed above, but you get the point. We are putting the athletes through certain movement patterns in order to expose potential flaws in movement quality or structural integrity.

You want to be able to meet the strength of one part of your body with another part of your body to drive optimal movement. This is what balance is all about.

What I mean by this “balanced movement” is, you will always be sacrificing optimal performance if you are structurally imbalanced because no matter how strong or mobile you are, your movement mechanics will be thrown off.

When your movement mechanics are thrown off you lose speed, athleticism, explosiveness, strength, and you also move with less efficiency which leads to quicker fatigue.

See how important this stuff gets?

If you’re not balanced you’re not moving correctly because the structures and limbs responsible for counter-acting another muscle can’t do their job appropriately.

When this happens, you start the domino effect that knocks down all categories of performance a certain percentage of what you could have otherwise accomplished had you been a balanced athlete.

Structural imbalances completely plague the hockey world. From a strength perspective, these are primarily in the hamstrings, rotator cuffs, quadriceps, and core.

The way in which hockey players move and which muscles they primarily activate drives these imbalances over the course of a competitive season. From a strength coaches perspective, working with hockey players is constantly correcting strength imbalances.

When looking for reasons why hockey athletes have structural imbalance issues, the trained eye doesn’t have to look so far.

For example, if you look at a hockey player, he/she is bent over at the waist for pretty much the entire game.

This shortens and tightens the hip flexors which can then lead to a whole host of postural issues including pain in the hips during movement (negatively affecting explosiveness), tightness in the hips overall (negatively affecting speed and agility), rounded shoulders (causing reduced shot power), shoulder impingement’s (causing shoulder pain), and a forward neck lean (at much greater risk for a neck injury during contact).

This is just one example of a cascade of events that kicks off with hockey players who don’t take their structure work seriously, or worse, those hockey players out there whose coaches have never even heard of structural integrity work.

During the hockey season, proper training often gets pushed back due to accumulating fatigue, travel, and scheduling issues — and this is exactly why structural balance work is a major priority in the early training phases of the offseason.

This is also why we highly recommend following our High-Performance In-Season Training Program if you’re looking to keep performance at top levels throughout the season and reduce structural integrity breakdown.

Let’s attack each strength-based issue holding you back from skating faster

#1: Quadriceps

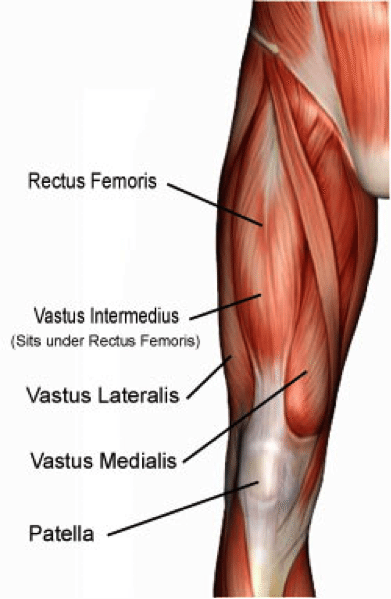

Almost every hockey player who first signs on with me has an over-development in the vastus lateralis in comparison to their vastus medialis oblique. The vastus lateralis is that thick muscle on the outside of your thigh, whereas your vastus medialis oblique is that tear shaped muscle on your thigh at the inside point just over your knee.

Almost every hockey player who first signs on with me has an over-development in the vastus lateralis in comparison to their vastus medialis oblique. The vastus lateralis is that thick muscle on the outside of your thigh, whereas your vastus medialis oblique is that tear shaped muscle on your thigh at the inside point just over your knee.

If you have been playing hockey and skating your whole life, odds are you have a big chunk of meat on the outside of your thigh, and not a whole lot of teardrop muscle going on at the inside of your knee.

That vastus lateralis gets overdeveloped through many years of skating, it’s a prime mover in the drive you use to push the ice away and propel yourself forward.

Correcting this difference is paramount to increasing your skating speed, explosiveness and agility on the ice — but also will play a huge role in knee stability (as the vastus medialis oblique is one of the prime knee stabilizers) which decreases the risk of injury to hockey players in the lower body drastically.

I’m telling you every hockey player needs to work on their VMO, even if it’s there and developed, they still should work on the strength of it (strength is different than size).

The carryover working on this will bring to helping you skate faster and the injury prevention risk is immeasurable.

Great options to work the VMO include:

Split Squat Variations

Step Up Variations

Front Squat Variations

Sled Drag Variations

These are all great movements and can be intelligently incorporated into your hockey training program to make you a faster skater.

#2: Hamstrings

Another big problem with hockey players is their glutes are much stronger than their hamstrings. Narrowing the gap between these two is something that must be addressed immediately entering the offseason.

Normally hockey players can see this just by simply looking at themselves, they have a big hockey butt and hamstrings that resemble a flamingo’s.

Hockey is a game of power expression, and in order to skate faster and more powerful on the ice you need to have a fantastic development of the hamstrings in relation to your glutes.

Hockey is a game of power expression, and in order to skate faster and more powerful on the ice you need to have a fantastic development of the hamstrings in relation to your glutes.

But, it isn’t just about doing some hamstring curls and leaving the gym, it’s a little more complicated than that.

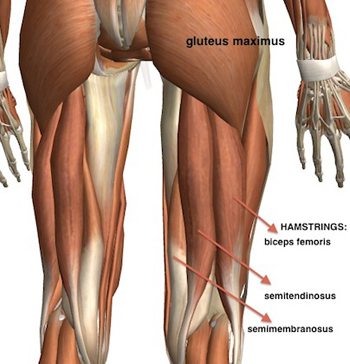

The hamstrings are a muscle group, not just a single muscle. Hamstrings consist of the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and the semimembranosus.

For those of you that know your kinesiology well, you will know that the biceps femoris is the primary muscle in pointing your toes outwards. This is where the problem sets in for hockey players.

Skating isn’t like running, your toes aren’t straightforward when you’re skating. Every single time you push off the ice your toes are pointing slightly outwards. This leads to a massive over-development of the biceps femoris in relation to the semitendinosus and the semimembranosus.

To have optimal balance and exert as much power as possible per skating stride, you need to bring up your strength in the semimembranosus and the semitendinosus.

Additionally, hamstrings also act as major knee stabilizers and help prevent lower-body injury risk. Check another box off for becoming both faster and more bullet-proof at the same time.

But, hamstring curls alone won’t do the trick.

Variation is key with training the hamstrings. Here are some great exercises:

Hamstring Curl Variations

Stiff Legged Deadlift Variations

Hip Thrust Variations

Two more things to make note of, hamstrings respond greater to lower rep ranges and higher intensities (below 8 reps), and keep in mind the placement of your toes, the way in which your toes are pointing trains different components of the hamstring.

As I said, variation is key.

Every phase you should be utilizing different options for a more complete development for your skating speed.

#3: Rotator cuffs

The rotator cuffs usually get overlooked no matter who you are. I test everybody who comes my way in the rotator cuffs and I often find either:

a) Very weak rotators.

or

b) Very imbalanced rotators.

It’s almost always a problem as not many people who don’t receive professional training advice know how to train them properly, if at all.

This is the only one of the four that doesn’t directly help you skate faster, but the rotator cuffs play a big role in hockey performance and have to be brought up to par.

Having a proper balance between your internal and external rotators drives shot power and accuracy.

One thing that is great is it is very hard to ever over fatigue the rotator cuffs. I normally train the rotators 3x per week if the athlete is lacking.

Depending on where the hockey player is weak, I find these exercises to address the issues the best:

Cuban Press

Scapula Retractors

Pull Up Variations

Rope Face Pulls

One thing that should also be noted here is that the rotator cuff responds very well to longer eccentric work — so incorporate these types of contractions into your programming where applicable in your periodization.

#4: Core

The core is an on-going issue with hockey players who don’t seek to balance themselves through proper training because hockey is what’s known as a “unilateral sport”.

Meaning, if you’re left-handed, you are always playing on that side and the muscles responsible for making you strong as a left-handed player continuously get overworked and overdeveloped through the years of hockey.

This has a ripple effect all over the body, but a big one in the core.

The core plays a role in transmitting power from the lower body to the upper body, and is in constant demand no matter what you are doing on the ice.

Skating, stopping, shooting, checking, saving — your core is involved in all of it. If you want to skate faster on the ice you need to correct your imbalances in your core. This is non-negotiable.

Where hockey players tend to have imbalances is within the lower abdominals and obliques.

The lower abdominals issue is normally due to improper training technique or training program design in combination with their chronic bent over stature during the game.

The oblique imbalance comes from the unilateral aspect of the sport, obliques rotate the body and every time you shoot you are always only activating the rotators (both accelerators and decelerators) on one side.

The core doesn’t have to be directly hit all the time. It receives massive stimulation and strength gain simply from big movements such as deadlifts, squats, front squats, chin ups, pull-ups, rows, and overhead presses.

Do these all properly and keep them in your training rotation, they play big dividends in the core development department.

But from a more isolated perspective, I find these exercises to work exceptionally well with correcting hockey player’s trunk imbalances and helping them skate faster:

Russian Twist Variations

Leg Raise Variations

Plank Variations

Medicine Ball Rotational Work

Recap on Increase Skating Speed Through Structural Balance

To wrap this up, even though this was a long article it still only touches on the importance of structural balance. I cannot stress how important this is to your performance and what kind of an impact it will bring to your game.

Athletes normally see something called “structural balance” and think of it as a boring topic.

But anybody who understands it and goes through an offseason program working on it knows for a fact that these components positively affect speed, power, coordination, acceleration, explosiveness, and decreased injury risk.

If you’re balanced, you’re a whole new player.

And structural balance has an enormous effect on your performance and longevity in the sport.

First, you need to be balanced, because anything you build on top of imbalances only creates greater imbalances. Solve that, and then move forward from there.

—

Here’s an example hockey speed workout similar to what you will find in our hockey training programs:

If you’re ready to become a faster skater check out our Next Level Speed program designed to help players become faster skaters. If you’re interested in becoming an all-around better and dominant hockey player I recommend checking out our off-season hockey training program.

—

Part 2 of this “How To Skate Faster” series can be found here: Fixing Muscle Tightness

Sine we teach kids to skate so early, when do we start to teach kids to start doing some of these exercises. I know it is a huge debate that spans over decades. What is your opinion. I teach a lot of these movements without weight.

I encourage all kids to play outside and play each and every sport they can. Doing this helps them learn how to properly move. One of the biggest problems with the generation growing up right now is they don’t know how to move, which is a breeding ground for structural imbalances. To give your kids the best chance at excelling in athletics and sport development you need to:

– Have them learn to move

– Have them learn to play

– Have them perform as many sports as possible

– Strength training at a young age should first begin with body weight and can progressively move to training with loads around age 13

Once you understand movement in sports, you understand that it demands perfect timing and perfect movement to be one of the best. Competing in as many sports as possible allows children to develop strong motor patterns and movement ability in all planes of movement. This translates perfectly to each and every sport.

Very young children should be playing, running, climbing, running backwards, throwing balls around, jumping, crawling and playing with their parents so they can learn from the parents movement patterns.

From being children to a more teenage age, in these years you should enroll your kid in as many sports as possible, but not at the same time. Do not overwhelm your kid, if your sport is hockey, keep it in every year, but the other sports should be rotated based on the season. Martial arts is one of the best things you can do for a child for increasing athletic ability and discipline. Additionally, martial arts helps to build strength with plenty of explosive body weight movements. Gymnastics is also excellent for the same reasons.

Following these guidelines, in my experience, will give your child the best base to build from.

i have 2 boys playing hockey they are very talented boys and the struggle is there speed if they gain speed I know they can play in the AAA elite teams

Hi Deano, how old are your boys? We can help them with their speed through training for sure. I’ve been using Dan’s training techniques for over a year now and my speed on the ice has increased dramatically.

Hey, this is a really neat guide, well explained and logically identifies key aspects of skating faster, definitely something I am going to need to work on in my own personal training. However I did notice something about the image of the hamstring muscles, it appears as though biceps femoris and semitendinosus have been labelled the wrong way round. Semitendinosus and semimenbranosus both run medially along side the leg, on the inside, and it is biceps femorus that runs laterally, on the outside.

Just thought I’d let you know!

Thanks for pointing that out Liam! We hadn’t double checked the image before posting (you’d think whoever made it would get it right), but we’ve uploaded a new image now.

Talking about the vmo my right leg vmo is good but my left is a lot smaller I don’t know but it is. My question is should I just work on left until I catch up or work on both.

Keep working both and the other will catch up

Hello–sorry for delay in seeing this, but it’s fascinating. On the VMO, assuming its importance to speed and acceleration, is that muscle also developed by riding one of the usual gym exercise bikes at the max intensity (level 20) for 12-24 minutes? I ask because the VMO on my legs always appear stronger (and pumped up) after engaging in such a bike workout (invariably, on the bike program that has you ultimately take on four sets of increasingly difficult hills). If I’m accidentally on the right VMO path with this exercise, I’d appreciate knowing it (and otherwise, if I’m not and this is counterproductive to building speed and acceleration on-ice, I’d appreciate knowing that too). Thank you again for the article and its excellent insights.

Hello there,

The bike within that training context can absolutely build quadriceps/VMO hypertrophy. For a ridiculous example, google Robert Forstemann.

Having said that, that type of longer duration, higher intensity lactic work does not carry over to the ice as optimally as designing your energy system work in a way that maximizes alactic-aerobic work.

The VMO hypertrophy is great, but I would rather build the VMO through resistance training work and use my energy system work as a way to build maximum conditioning transfer on the ice.

My kids are IP1 and novice do you have anything for that age or are they to young still.

Hi Stephane, we have a new bodyweight program available here in a week or two: https://www.hockeytraining.com/programs/