Balance training is something that has made its waves through the hockey training industry, but what it’s really trying to accomplish is something more accurately described as proprioception.

Proprioception represents how the body reads information from various body parts in motion, as well as what’s going on in the environment around your body.

This information (proprioceptive feedback) is the language that your nervous system uses to figure out what is happening with your body and what move it should make next in order to accomplish whatever task you’re trying to complete.

Proper Application and Misapplication

“Balance” training is described by trainers to produce more proprioceptive feedback than barbell exercises do.

As always, more is not better. Meaning, there is a definite point of diminishing returns when it comes to these ideologies.

I’m not saying proprioceptive work is bad because it’s not. But like anything in strength and conditioning, the magic is always found in the application of the tool – and not the tool itself.

For example, a seated hamstring curl uses a seated position and a fixed movement pattern that you are guided through by a machine; not a whole lot of proprioceptive feedback there. All you get essentially is “hamstring curl down on the thing and the thing will do a half circle to the bottom and half circle back up” – not so complicated from a proprioceptive/co-ordination perspective.

On the other hand, you could perform a lateral reaching lunge with dumbbells. This will require coordination through some major muscle systems in your body (hips, core, hamstrings, quadriceps, posterior chain, etc) and use these related muscle group in a way that is more consistent with the skating motion (for example, teaching the co-ordination of the hamstring to extend the hips while simultaneously controlling knee flexion).

This is much more complicated for the nervous system to grasp and demonstrates very clearly that the seated hamstring curl is less proprioceptively challenging than the lateral reaching lunge with dumbbells.

The hamstring curl machine stabilizes all movement, so that immediately reduces the proprioceptive feedback demand from your body (your body won’t need to calculate where you are in space or what’s happening in your environment if you’re just sitting there going through a fixed movement) in comparison to the reaching lateral lunge that is not stabilized by anything.

Not surprisingly, this is where the seed of “unstable surface training” comes from. The lateral reaching lunge was not stabilized, so some trainers a couple decades back that it would be a good idea to make it even less stable by throwing you on a ball or wobble board or something.

That theory sounds alright on paper, right?

Make it less stable to force for proprioceptive feedback and therefore “get more out of the exercise”

That can be easy to sell in marketing but is a far cry from optimal programming within sports science. Just because a high amount of neural information (proprioception) is being utilized during a movement, it does not mean that the information is meaningful.

The neural language your body is utilizing must have some degree of transfer/specific carryover to your sports demands – if it doesn’t, you’re just learning how to do circus tricks…not become a better hockey player.

Using this same logic, we should be doing our bike interval sets on a unicycle for “better results” – which we both know is crazy.

You might laugh at that statement, but it follows the exact same logic these people are trying to sell you when they make you balance on one leg on a stability ball while shooting a hockey puck.

Hockey doesn’t work like this, from a sport-specific proprioceptive perspective, hockey athletes require the skill of transferring maximum levels of force from the ground up through your extremities and/or an implement (hockey stick) through stiff body segments.

This is the proprioceptive language that will have carryover to the ice.

I also want to make it very clear that the seated hamstring curl isn’t a “bad” exercise, it’s just not the tool you would use to drive proprioceptive demand.

Different tools have different applications and any real coach who understands both the science and art of program design recognizes that and only uses the tool where it fits best.

On that note, let’s talk about the misapplication of tools – and it all begins with a misunderstanding of the important terms; balance and stability.

Understanding the Difference Between Balance and Stability

I think a lot of the misapplication of program design doesn’t come from a bad place of people just wanting to make money – I really do believe people mean well and just want to help the younger generation become better hockey athletes.

The problem is if we don’t understand the definitions behind the terminology that we are using, we are bound to make mistakes in the program design process.

Balance training should never be mistaken for stability training, and yet I see these two terms utilized interchangeably on a regular basis.

Balance means the stability produced by the even distribution of weight on each side of the vertical axis. In action, this means to bring about a state of equilibrium (a state of balance between opposing force).

Stability is the quality, state, or degree of being stable, as in the following:

- The strength to stand or endure (e.g. Rigidness)

- The property of a body that causes it when being acted upon by other forces to develop its own forces to restore the original condition (e.g. Stand your ground while being pushed)

- The ability to resist forces tending to cause motion or change of motion (e.g. being able to come to a clean stop and not have your momentum continue to move you forward on the ice)

- The ability to develop forces that restore the original condition as soon as possible with taken away from the original condition (be able to return to a strong base of support on the ice and/or ground after being pushed or body checked)

Basically, balance is you manipulating opposing forces to create a stable state over a base of support – whereas stability is the control of unwanted motion to restore or maintain a position. Read that sentence three more times, and then think about it for a moment.

What would have more transfer to hockey performance?

“Balancing” on an object, or creating strong “stability” in an athlete so that they are never taken off balance on the ice – and when they are, they have the physical qualities to return to their original condition anyways?

Things start becoming much clearer when we break them down, don’t they? Of course, you’re going to want stability, because hockey athletes are never subjected to an unstable environment out on the ice – it is always a stable environment.

Thus, stability training is incredibly more beneficial for hockey athletes in comparison to balance training.

Balancing requires the transfer of low forces to maintain an equal state, whereas stability requires the transfer of high forces to create rigidity. If you will recall from above, hockey players need to transfer high levels of forces from the ground up to create a sport-specific result, you can’t do this with balance training.

Just Think About A Triangle

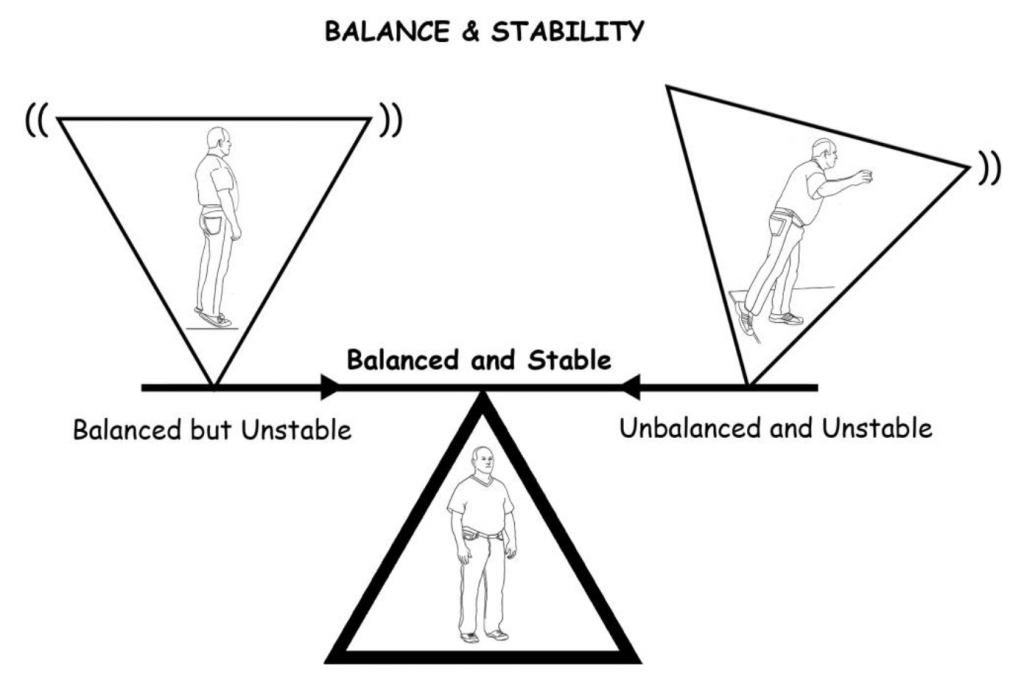

As you can clearly see below, triangles allow us to drive this point home in a very simple to understand manner.

The stable triangle (or, stable athlete) can withstand any force driven through its system; it is both strong and balanced.

The balanced triangle, on the other hand, can’t take any force unless you apply it perfectly on a vertical axis (think about it like applying pressure to an egg, it is only strong on the top and bottom).

If you think of a hockey player like a triangle that responds to high levels of multidirectional loading – then you must train it on its base and not on its point.

When the triangle is balancing on its point, you simply cannot apply enough load to create any significant training stimulus to occur.

The weight you would need to use to train on the triangles tip would be much lower than your actual strength capacity – and therefore not create a stimulus for any adaptation to occur (strength, speed, hypertrophy, conditioning – you name it, you wouldn’t be able to train it effectively without a stable foundation).

This is stability vs. balance – on the right you have a balanced athlete who is not stable, the slightest amount of force will knock this athlete over (not exactly desirable in hockey!).

Whereas on the left you have an athlete that is both balanced AND stable, and due to his/her stability, they can both create and absorb high levels of forces out on the ice.

Future Direction

There is nothing for you to do from an unstable position (e.g. stand on one leg on a BOSU ball) except stand there, balance, and create non-important proprioceptive information that your nervous system will never need out on the ice.

Hockey athletes cannot transfer high levels of forces or maintain their position in the face of hard physical contact from a narrow or small base of support; you would be left completely at the mercy of the physical forces in your environment (e.g. getting absolutely smashed out on the ice).

REAL balance training for hockey must concentrate on creating stability so that proper athletic positions can be maintained and forces can be transferred through the kinetic chain with maximum power output.

This means it must be trained in a stable state – or to put it another way, if you want real strength and stability out on the ice… get a coach who can design a proper strength training program for you and stop playing around on the wobble boards.

Do you play hockey? Hockey players “balance” on a thin, tall piece of steel. Not only is the skate an unstable piece of equipment, but the ice is a slippery and unstable surface as well. In fact, hockey players are constantly “balancing” on one leg in game and practice situations. Unless you are a”bender” or standing in place the “triangle” does not apply. You are correct that stability training is important for hockey players, but balance training is very important in sports such as hockey and ski racing. Try standing on one leg in a pair of skates and stick handle/shoot and your appreciation for “balance” training will improve.

I’m sorry Toby your comment is laughable. If you’re needing to balance on your skates you need skating lessons. Anyone comfortable with skating has no troubles “balancing” on what you’re referring to as the “thin, tall piece of steel” (a laughable quote). The ice being a “slippery and unstable surface” is even more laughable. I’m sorry but the ice isn’t slippery when you have two skates on your feet, and as far as I know the ice stays in one place and isn’t unstable in any rink I’ve ever played on.

Hi, Coach Dan. I’m interested, what players from KHL have you worked with?

Hey Valentin,

I don’t disclose the information on who I have worked with unless I have been given written permission to do so — organizations keep things pretty tight for copyright and business reasons so I tend to stay away from it.

i need help with speed

Check out this article that will help you get faster: https://www.hockeytraining.com/speed/