One of the most common questions I get when working with hockey players, whether it’s in the NHL, college, junior, or high school, is this:

“Why don’t you program Olympic lifts like cleans or snatches?”

It’s a fair question. Olympic lifts have long been considered a staple in strength and conditioning programs. But that belief comes from football culture, not hockey. Formal strength and conditioning was built in the football world, and some of those traditions (like heavy cleans and snatches) have bled into other sports where they don’t always make sense.

The truth is, Olympic lifts aren’t the best way to build speed and power for hockey players (and likely football players, but this is a hockey page so let’s stay focused!).

Here’s why:

They’re Too Technical To Build Power Today

Olympic lifts are extremely technical. Before you can move heavy loads at high velocity (aka the actual equation for power – force x velocity) you need to spend weeks or even months just learning proper technique.

Think about the progression:

- Learn to deadlift from the floor properly with a barbell

- Learn position one (bar at the hip, slight knee bend)

- High pull from position one

- Clean from position one

- High pull from the hang

- Clean from the hang

- High pull from the floor

- Clean from the floor

That’s a long process before you even get to the point of training power. During those weeks, you’re not building speed or explosiveness, you’re just learning a skill.

In contrast, something like a loaded jump or a med ball throw lets you train for power on day one. No steep learning curve. No wasted time.

You could make the argument that you could just do sprints, loaded jumps, and medball throws to train power while you’re learning the Olympic lifts. But, if those movements help improve your power, why wouldn’t you just continue doing them instead of Olympic lifts?

Limited Mobility Due to Sport Demands

Olympic lifts demand mobility that most hockey players simply don’t have due to the nature of the sport and common injuries.

Shoulder flexion: Try this quick test. Sit on the ground with your back against a wall, hug your knees to your chest, and then try to raise your arms overhead without arching your back, bending your elbows, or widening your hands. If your thumbs can’t touch the wall, you lack the overhead flexion needed for safe snatching. This is a common issue in humans in general, but especially hockey players with constantly being bent over onto their stick.

Wrist and finger extension: Hockey players take countless impacts to their hands from falling on the ice, running into the boards, or blocking shots. That often limits wrist and finger flexibility, making it impossible to safely get into the front-rack position for a clean.

If you lack that range of motion, at best, you limit your power development because your technique will always be subpar. At worst, your technique will be so bad that you compensate and cause injury up or down the chain. In the gym, the first rule is to reduce the chance of injury. The easiest step to that is making sure you don’t get injured in the gym!

Surfing the Force Velocity Curve

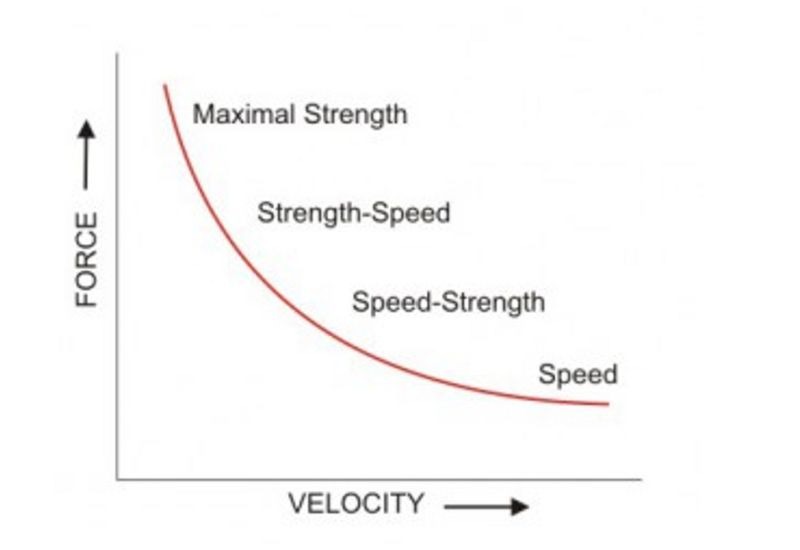

Olympic lifts sit in the middle of the force-velocity curve, in the “strength-speed” or “speed-strength” range depending on load. But they aren’t the only (or best) way to train that quality.

Image from Simplifaster.com

For strength-speed:

- Dynamic effort lifts (squats, trap bar deadlifts, bench) at 50–65% of max, lifted explosively

- Barbell or landmine push pressed (if you have the requisite overhead flexion)

For speed-strength:

- Loaded jumps (barbell, trap bar, dumbbells, or weight vest)

- Medicine ball throws and tosses

All of these allow you to immediately train power with minimal technique barriers. As stated in the first point, with Olympic lifts, you might need months of technical practice before you start seeing real transfer to speed on the ice.

The Real Purpose For Power Training

Yes, power matters in hockey. But what players really need is speed.

Power training is valuable because it indirectly supports speed and has been historically easier to measure (i.e. accurately measuring broad jumps, vertical jumps, etc. versus accurately timing sprints). But, nothing replaces actual sprinting for speed training. If you want to skate faster, you need to train faster.

That means:

- Short sprints for acceleration

- Longer sprints for top-end speed

- Loaded sprints for force production

- Change of direction and transitional sprints (2-shuffle to sprint, alt. 3x crossover to sprint, etc.) for agility

Power exercises are important, but sprinting directly trains the quality that hockey players rely on most: speed.

Closing Thoughts

If you enjoy Olympic lifts and they work for your body, there’s nothing wrong with doing them, just don’t mistake them for the best way to build hockey speed and power.

If your goal is to be the fastest, most explosive player on the ice, you need to train like a hockey player, not a football player. That means choosing exercises that maximize transfer to the game, reduce injury risk, and deliver results immediately, not months down the road.

If you want a proven system that does exactly that, check out our In-Season Domination Program designed to keep you fast, explosive, and dominant all season long.