We all know somebody who has some really strong lifts in the weight room, but just can’t seem to put it together athletically out on the ice. That strength just doesn’t seem to be transferring to their speed, agility, quickness, or even shot power.

One the other hand, we also all know somebody who moves quite well and has great endurance, but gets knocked off the puck more often then they should due to their weak stature.

What every hockey player needs if they are looking to jump to the next level of their performance or jump up to the next level in competition is the combination of both speed and strength.

This is where power development comes in. The players who can balance these two effectively and efficiently are the ones who make the greatest impact out on the ice, it’s the best of both worlds.

When I have talked about strength and power in the past through previous blog posts or on Hockey Training videos, some people confuse the two and think they are identical qualities which they most certainly are not.

Strength and power are their own individual qualities and although power development can contribute (minimally) to absolute strength and absolute strength can contribute (more so than power’s contribution to strength) to power development, they are trained very differently and mean different things to the hockey athlete.

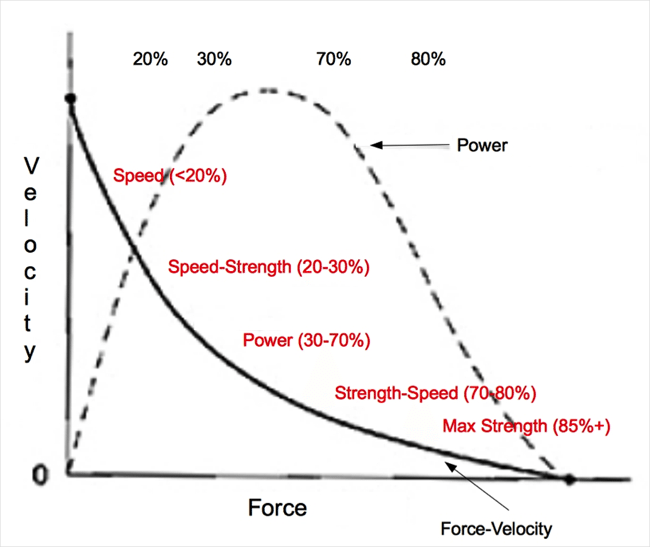

Where power and strength part ways from a sports science perspective is that power is the rate at which you can produce force. Whereas absolute strength is all about total force production, the speed at which you reach that force production is irrelevant.

Power = Force x Velocity

The faster you can create a ton of force, the more powerful of an athlete you are. Power is all about your rate of force production. The faster your neurological system can recruit all of those high-threshold motor units and create muscular contraction, the more powerful you are.

For example, if two athletes have an identical max squat of 400lbs, they are of equal strength levels. But if one of the athletes can squat their working weight of 160lbs (40%) to 240lbs (60%) much more explosively, he is the more powerful athlete even though they have identical max strength values. We’ll talk about why I chose these working percentages below.

As you can see demonstrated above, power works on a bell curve and optimal training values include weights between 40-60% of your 1-rep max performed explosively.

Why Does Power Matter To Hockey Players?

Hockey is an incredibly power dependent sport.

The faster and more explosive you can express your strength out on the ice, the better. Power has a direct transfer into your shot power, puck release, how much force you will be able to produce in a shot with minimal wind up time, body check force, agility, explosive starting speed; among all other things high force/velocity on the ice. And for you goons, it’ll definitely help you fight.

There is a huge amount of direct carryover from an increased power development to many facets of the game and how well you are going to be able to express your skills on the ice when it matters most.

I want to make it very clear though that when it comes to training for power, you do not want to be thinking about power lifting. This is especially true because despite its name, the sport actually doesn’t require any power specific training.

The sport was given that name decades ago, and as the research kept coming out it became more and more obvious that power had nothing to do with power lifting. Sure it can help a bit, I mean if you’re explosive you may be able to speed your way through a sticking point in a lift (for example, if you have trouble locking out the bench press it may help you if you’re more explosive out of the bottom of the lift so that you have momentum on your side once you reach the lock-out phase of the lift). But this would likely only be with some training loads, and not at the actual competition meet where it would matter where you have a Personal Best loaded up on the bar.

Power lifting is a 1 rep max sport and any true 1 rep max is not explosive and therefore is not power dependant. Instead, it’s maximal force dependant. If we wanted to be as accurate as possible the sport should be called force lifting.

An example of power in power lifting could be seen in the deadlift. A more powerful lifter could get it off the ground faster than a less powerful lifter, but that doesn’t mean he is stronger or a better lifter or has a higher 1 rep max. Just has some better explosive starting strength.

But that’s neither here nor there.

The main point I am trying to get across here is if you’re a hockey player looking to improve power development, don’t look to power lifting as a means to do so for two main reasons.

#1. It’s not sport specific

#2. You won’t actually improve your power output by any meaningful amount

To differentiate the two, training with loads 75-100% 1RM will contribute to an increased max strength while training with loads 40-60% 1RM performed explosively will result in an increased maximum power.

Definitely apples and oranges here.

Power training is extremely nervous system dependant and therefore you will need to take longer rest periods for complete recovery to be able to reproduce the same level of explosiveness (thus, power) again. This is important to care about because when exclusively training for power you have to keep your velocity high. Power should be trained near 90% velocity which means you need to be explosive with every single rep you do.

Keeping that same level of explosiveness is crucial because once it’s gone, you’re not training power anymore. Simply put, if you’re not moving explosively, the adaptation you are trying to stimulate is being thrown into a grey area with other conflicting adaptations (strength for example).

In order to properly training for power, we now know:

• You need complete recovery between sets (2-3 minutes or more depending on intensity and training style).

• You need to be moving explosively every single time.

• Resistance should be in the 40-60% 1RM range.

• If we aren’t following these guidelines, we are no longer training for power.

So how do we connect the dots between these guidelines and start training for some more power that’s going increase our performance out on the ice?

A great way to approach this is with longer rest periods during training and utilizing a very short rep range. To maintain the quality of technique and required level of explosiveness, your rep range for power development should never exceed 1-5 reps. Anything beyond that will result in technique and explosiveness breaking down and you will then no longer be moving with enough velocity to properly train the muscles for power.

For example, if you were to do box jumps for 10 jumps straight at a moderately difficult height, you would be not nearly as explosive on jump number 10 as you would be for the first few jumps, even with a long rest period.

Additionally, even if you’re doing the proper amount of reps for a given set, if you lose your explosiveness during that set you should discontinue it immediately. You never want to lose that “pop” in your movement during power training. Quality of movement and real explosiveness is a must here.

The Role of Core Strength and Stability in Power Development

Core training can sometimes be over-hyped by some trainers. If you talk to some hockey coaches, you’d think training the core will pay all your taxes, increase all your lifts by 100lbs, score you goals without trying, and cure cancer.

In all seriousness, the core’s contribution to hockey performance is a big one (and will be the subject of a future blog post all by itself), but some trainers take it too far and demonstrate a real lack of fundamental knowledge behind sport science. For example, doing push ups or squats on a BOSU ball to “engage the core” is completely idiotic and will not enhance the training effect nor will it improve the carryover from those movements to the ice.

When it comes to the core’s contribution to power there is some great carryover to hockey being that power is created from the ground up and that it is your core that allows you to properly absorb, stabilize, accumulate, and transfer forces out the extremities. The core’s strength and stability is a true foundation for multi joint, multi-planar powerful movements.

To paint a picture here, if you have incredibly well-developed legs and arms but an under-developed core, your speed and shot power will be drastically reduced because you will not be able to express the force potential of your legs and arms. This is also an injury risk — if your legs and arms are stronger than your core can handle (which stabilizes your spine) then a powerful movement could end up in injury.

You can think about it like shooting a cannon out of a canoe, the canoe simply can’t handle the amount of force that’s created and is going to breakdown.

Core training is not the “be-all end-all” to sport performance, but it certainly plays a significant role. Where most trainers go wrong is underestimating how much core development is being effectively trained through movements like dead lifts, chin ups, squats, split squats, and row variations.

Think about it, the core’s primary role is to stabilize the pelvis and spine. How much core strength and stability is required to keep your spine straight and stable throughout a 500lbs dead lift as opposed to doing a crunch on a stability ball?

Don’t get me wrong, core isolation movements aren’t a bad thing, but they shouldn’t be the foundation of your training plan or even the base of a whole workout.

At the end of the day, if you’re core strength is lacking you will need to bring this up to par to maximally express your power both on the ice and in your training.

Power Training for Hockey

Power training for hockey has to involve the most important training principle in sport science, specificity. The principle of specificity is a principle of training program design and it represents the idea that the movements that you perform in the gym have to, in one way or another, contribute to improving a performance parameter that will transfer to the game on ice.

In other words, it has to be sport specific from a scientific standpoint to justify training use.

This means the movements you perform should be similar to the game of hockey in what joints are involved, what muscle groups are involved, the planes of movement, force production involved, the speed of movement, and the duration of the movement.

Additionally, just like other muscular adaptations (strength, hypertrophy, endurance, etc.) power development is local. Meaning, if you train the lower body for power it will not transfer to the upper body and create a global response. You need to involve both the upper body and lower body in your training program design in order to create total body power development, which is exactly what hockey players need. This means adding a box jump day into your plan isn’t going to cut it for maximal transferable development of performance enhancement out on the ice.

Here’s an example lower body power workout that is great for hockey players:

A1: Sub-maximal load BB squats (40-60%): 6 sets of 3

A2: Box jumps: 6 sets of 3

Rest 10-15secs between A1 and A2 and 3mins after A2.

B: RKC plank: 3 sets of 4-6 reps (each rep 10secs contraction, stay in plank position for 10secs in between reps)

The above is a perfect example of the “Contrast Power Training Method” for hockey players. Contrast training is an extremely effective (and difficult) philosophy of training which is defined by a strength training movement followed up quickly by a speed movement or sport specific skill.

This type of training excites and activates the nervous system to its limits recruiting the greatest amount of high-threshold motor units which transfer over into the speed movement or sport specific skill. The rest you take between the two needs to be short enough for transfer ability but long enough so you can still perform the movement well, 10-15secs is your target and never go above 20secs. Beyond that, transfer level is low and you’re defeating the purpose of your power training.

The contrast method is just one of the philosophies which is effective for power development in hockey players, other power training modalities include:

• Plyometrics

• Ballistic movements

• Reactive training

• Olympic lifts

• Low load band / chain work

• Low load sled work

• Sprint variations

• Jump variations

• Medicine ball throws

An important note to make on the programming of your power training is what’s known as “adaptive decay”. We know that for optimal sports programming, proper periodization is a must and adaptive decaying is just one of the many reasons for this.

Athletes cannot work on everything at the same time, what happens is they become sort of a “jack of all trades master of none”. Meaning, you can’t meaningfully train several qualities at the same time and expect to get good at all of them. You cannot train for size, strength, endurance, power, mobility, speed and skill all at the same time and expect to have equal levels of improvement in all of them.

The body will go “ok I don’t know what you want me to do so I’m going to get a little bit good at all these instead of really good and any one of them”. This is what periodization is all about, NOT DOING THIS!

Proper training plans need to address phase potentiation and the stimulus recovery adaptation to maximally gain the qualities you are trying to achieve during training. Where smart programming comes into play and what separates the good coaches from the bad is maintaining the quality you gained in the last phase while you work on another quality.

What adaptive decay means is that all fitness characteristics also have varying levels of decay rates. Meaning, if you focused on strength in your last phase and you do no strength work in your next phase, that adaptation you gained in the last phase has a decay rate where you will begin to lose that quality.

Smart programming minimizes this so you can become meaningfully good at everything while working on one quality at a time and not losing the previous qualities, this is how we graduate from not being a “jack of all trades, master of none” and instead move towards being a true master of all trades.

Without going into the specific details of all decay rates (hypertrophy, strength, endurance, aerobic capacity, etc.), because this is a power blog I am going to tell you that power is the most sensitive training quality to the effect of decay.

Power only has an estimated 2-week window before you begin to start losing that quality.

Meaning, if you train power for a training phase and then do zero power work for 2 weeks — you will begin to start losing your maximum ability to produce power. Which in turn means that your speed, explosiveness, and agility out on the ice will all start to decrease in potential.

Crazy, right?

So, when programming for hockey keep power somewhere in there year-round so you do not begin to lose it, this is especially important during the season.

I hope this blog post helped shed some light on the contribution that power has to hockey performance, here are some takeaway notes of importance:

• Genetics play a big role in power potential

• Power = Force x Velocity

• Power is different than strength

• To train power, you have to train explosively

• Keep the reps low

• Keep the rest periods high

• If an athlete develops great power, he/she is bridging the gap between combining strength + speed

• To maximally express the power you have you need core strength and stability

• You must move with the intention of max acceleration when training for power

If you know of any hockey players who may benefit from this article please share it with them, and feel free to post in on Facebook, Twitter, or wherever else you can think of!

Hi, it’s a very interesting post. But how should you periodize a program ? I’m playing hockey all year long so I don’t have an off season. How should you periodize in that situation. I feel like I’m training and I’m going nowhere at all!

Training and going nowhere at all most likely has more to do with your recovery rate and nutritional habits. You can only make progress based on what you can recover from. Any training should provide at least some results, but since you seem to be standing still the first place I would look is into your meal plan design and recovery from exercise.

As far as periodization goes to discuss a full hockey periodization year for somebody training year round goes a little outside the scope of the comment section but sticking to power, power works should simply be incorporated into your weekly training regime at a recommended 2-3x per week on average.

It doesn’t have to be it’s own session, it can be thrown right into your speed/conditioning work or right into your resistance training. Just be sure it gets in there.

I am doing the Speed and Conditioning workouts as outlined in the Next Level Speed. I am starting phase 3, and really liking it. What is the best way you recommend to incorporate Power into that workout plan? or do you recommend not doing the two of them together? Thanks!!!

Speed is power my friend. You just now have a much better physiological understanding behind what you’re doing now after reading this.

You’re already hitting up both upper and lower body power quite plentifully during the week running my Next Level Speed system. In all honesty, you’re good to go.

But if you really wanted more, I would suggest only adding 1 movement in at the beginning of your resistance training sessions aimed at optimal power development. Ideally this would be based on the muscle group that you’re training that day and not be any of the exercises included in NLS so you get a greater variation in development

Should I still train for strenght or should I only do power training now?

I am doing a bunch of training but need help on my eating. Can you make a blog post about what you should eat on a day-to-day basis

Check out our YouTube channel… we’ve got lots of useful info on nutrition there: https://www.youtube.com/user/officehockeytraining

Thanks