Welcome to the Hockey Agility Training guide. This is a comprehensive guide to hockey agility and learning how you can properly train your agility to translate to becoming more agile on the ice and during hockey games.

Before digging into all of the content below, I highly recommend also downloading this FREE explosive speed package that contains workouts and further information not found here.

Whether you are a hockey player looking to learn how to improve your agility or a coach of any kind looking to help out hockey players, this is the hockey agility guide you will want to read and bookmark.

This is a very in-depth guide covering everything hockey agility training related, so we’ve created a table of contents that you can come back to and use to resume your reading. Enjoy!

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is Agility?

- Agility as a Unique Skill

- Breaking Down the Components of Agility

- Strength Types and Agility Transfer

- Technical Breakdown of Movement Mechanics

- Testing Agility in Hockey Athletes

- Coaching Methods for Hockey Agility Training

- Rehearsal vs. Reactive Agility

- The Power of the Mind

- Warming Up to Maximize Agility

- Agility Training Warm-Up

- Hockey Agility Drills and Workouts

- Conclusion

Hockey Agility Introduction

In hockey, changes of speed or rapid and decisive changes of direction result in a break, a score, or a defensive stop that can change the momentum of the entire game.

Agility is a highly unique attribute that requires multiple physical and cognitive qualities such as explosive strength, starting speed, reaction time, and rapid decision making.

My goal with this project is to create the most comprehensive breakdown of hockey specific agility training in the market today and make it very clear what are the most critical components of agility (both physical and cognitive) and layout how you can create optimal agility in yourself or your teammates in an organized and understandable way.

Throughout this article I will be thoroughly describing the physical, technical, mental, and even tactical aspects required to create both well-rounded and effective agility in hockey athletes.

Specifically, this article will help athletes and coaches understand, test, measure, and implement immediate coaching strategies and cues to enhance on-ice agility.

Further, I will be touching on long-term periodization of agility development and how you should be working through an entire program design in order to improve this often under-developed and under-trained category of hockey performance.

What is Agility?

The ability of a hockey athlete to change initial direction to a predetermined location and space on the ice (or the track/field since dryland work is where we will be doing most of our agility training) is known as Change of Direction Speed (CODS).

However, it is the perceptual-cognitive ability to react to a stimulus such as the defensemen or the movement of the puck in addition to the physical ability to change direction that provides a true definition of agility.

In many sports, but hockey especially, athletes do not have the time nor the open space to reach true top speed levels during a game.

The constant chaos of reacting to the game and playing on a surface as small as a standardized rink requires hockey players to decelerate and then reaccelerate in another direction as rapidly as possible whilst maintaining or regaining as much momentum as possible.

This readjustment of the athlete’s momentum can occur during either an offensive, defensive, or goalie-specific task. Agility and kinesthetic body awareness is relevant for all hockey athletes.

Plenty of research has indicated that an athlete’s lower-body response time may differ depending on whether the athlete’s stimulus-response requirement (tactical situation) is offensive or defensive.

The exact reason for these varying response times is not yet known, however, the processing strategy (which varies depending on gender and environment) can influence the time it takes a hockey athlete to physically and cognitively respond to the situation.

Oddly enough, scientists have hypothesized that offensive response requires information to move across both hemispheres of the brain, whereas defensive response allows the processing to occur on only one side.

This may sound overwhelming, but the conclusion is surprisingly common-sense. Just like you would train both the left and right side of the body, hockey athletes should utilize drills that require processing across both hemispheres of the brain. This creates “balance” in your mental agility, which then translates immediately to greater balance in your physical agility.

To give you a quick preview, this means when developing drills to enhance agility performance, it is wise to ensure some of the drills involve moving in the opposite direction of the cue.

For example, it is very common for coaches to involve “move in the direction that I point” type of agility drills, but, we are learning now that it is just as important to utilize “move in the opposite direction that I point” drills to ensure we are maximizing both offensive and defensive agility awareness.

Although similar, offensive and defensive agility are two different things; and when broken down to their finest level of specificity, the drills are slightly different from one another.

With this powerful knowledge that the brain processes offensive and defensive responses differently, we must consider the environments and tactical situations that occur and train not only the physical pathways of accelerated muscle contraction, but also the perceptual-cognitive pathways.

As you can start to see now, agility is much more complicated than just “Hey, kid! Go run on that ladder for 30 secs” – it is multifaceted both physically and mentally.

Beyond this, we must incorporate ways to train each quality in a logical, progressive manner to ensure continued progression so that we are not just throwing a bunch of random cognitive and physical exercises together and pretending to call it a well-designed hockey program.

You need to be aware of how to test agility, how to measure agility, and then pin-down what factors are going to be most impactful for that athlete so that you can improve agility at the fastest possible rates.

Having said all of this, a sharp mind isn’t anything without a sharp body. We can’t overlook the importance of biomechanics, strength, power, mobility, and all of the other physical qualities that support the performance of CODS. Doing so would be an incomplete approach, and that’s not something we’re about here at Hockey Training.

Agility training does not need to be complicated. The science can be complicated at times, but that’s ok. Something I always say to the coaches that I educate is:

“Hard on us, easy on the athletes”

Meaning, just because the “why” is complicated, it doesn’t mean that the “how” has to be for our hockey players. If they just execute, they’ll get the results anyways. Sophisticated program design doesn’t mean complicated program design.

Although, the coordination necessary for advance agility training may preclude it from the basic training protocol of trainees who lack basic coordination and strength.

But, a trainee needs great speed strength to be agile anyways, so they still have much they can work on before doing the “higher level” agility drills.

That is to say, a trainee needs great starting strength as well as a high level of absolute strength to create maximum instantaneous fiber recruitment explosive strength; as in the ability to use recruited fibers till they are no longer needed and still be able to recruit more.

To be athletically agile, these strength components (starting strength and absolute strength) are necessary and will work together.

For instance, halfbacks, gymnasts, acrobats, and others have physiques that are impressive cosmetically because of the demand for agility within their sport or activity.

So, some agility training or agility related movements can be beneficial not only for agility (obviously), but also for body composition enhancement. Usually these movements are put near the beginning of a training protocol or as part of an active warm-up.

Remember, coordination suffers as the body fatigues, so agility work should be done early in resistance training workouts or done as “drills” entirely on their own day.

Agility as a Unique Skill

Ever since I got into the strength and conditioning world, the biggest focuses of athletic development have been on improving strength, size, fat loss, power, speed, and overall conditioning.

Very little attention has ever been paid specifically to agility and quickness, even though these two skills as just as essential to any sport as the rest of the above-mentioned skills/qualities.

To explain this further, when you analyze the data from the top 10 performers in the 40-yard sprint from 2012 and 2013, only two of them made it into the top 10 in the 20-yard shuttle run, which is an agility drill.

If you look at the 3-Cone drill (which is another agility drill) the outcomes were similar, except only one of the top 10 40-yard sprint performers broke the top 10 in the 3-Cone drill.

What does this type of placing and data tell you about athletes?

Agility is unique.

It’s a physical quality and skill all by itself – general strength, speed, power, and these other qualities will all have some crossover into agility, but you still need to train agility by itself to get optimal agility results.

It is its own unique ability. High-velocity direction change is about a lot more than just strength and power, especially when you throw in an environment as chaotic and unpredictable as a hockey game.

So, what are the components of agility then?

What makes it different than just running?

Well, it begins with the “Plant Phase”

Understanding the Plant Phase

When you understand the magnitude and direction of ground-reaction forces applied during the plant phase when changing direction, this will give you heavy insight into the complex physical requirements needed to become optimally agile for hockey.

The plant phase (as seen above) involves forces that decelerate, change direction, and reaccelerate in less than two-tenths of a second. The circumstance of pre-planned change of direction, or, reactive change of direction – can modify the mechanics of the step involved during the plant or change-of-direction step.

When you know your kinetics (forces and joint moments) as well as your kinematics (joint angles and joint velocities), you can create a logically progressive periodized agility training train than gradually increases intensity and specificity of hockey-specific agility from both a physical and cognitive perspective.

Various hockey agility drills in combination with specific coaching cues can be used continually over time to enhance overall agility in hockey athletes.

Breaking Down the Components of Agility

As you can tell by now, agility, although described as one word, is the combination of many factors at play all working synergistically with one another to give you the seamless fluidity of movement you need out there on the ice to dominate.

Let’s have a look at some of the “building block” factors that make up what we refer to as “agility”.

PERCEPTUAL-COGNITIVE

- Visual scanning

- Anticipation

- Pattern recognition

- Knowledge/experience in the situation

- Reaction time

CHANGE-OF-DIRECTION SPEED (CODS)

- Body position

- Foot placement

- Stride adjustment

- Body lean

- Posture

- Sprint speed

- Leg quality specific to COD step

- Reactive strength

- Power output

- Strength (concentric, isometric, and eccentric)

Because this is both mental (perceptual-cognitive) and physical (CODS), athletes and coaches need a highly layered approach to their training in order to gain an optimal response.

One thing I can tell you from experience is that enhancement in agility (as a “whole”) will normally lag behind the enhancements of the categories that make up agility.

For example, you will likely see increases in things such as strength, power, and mobility at more prominent and linear rates then you will see agility increase.

This isn’t to say that building up those qualities won’t create a positive effect on agility, it just means that I almost always see a “lag time” between an athlete’s newfound capabilities and the time it takes in order for them to turn those new capabilities into usable agility.

It’s very important that you respect and understand that there is a lag time between capacity (building up your individual qualities) and ability (expressing improved agility out on the ice).

Why?

Because when you understand and respect the necessary lag time, it allows you to trust your plan and stick to it for the long-term.

Agility isn’t something that happens overnight, you need to work hard on all of these qualities, and then allow for lag time, and then finally express your newfound ability after all your hard work and patience.

Agility demands adaptations in muscles, ligaments, tendons, energy systems, movement mechanics, and overall cognitive ability. This stuff takes time, so give it time.

Or, put another way, don’t slack off your entire season and then say “Hey Coach Garner! I have tryouts in a month, what should I do?”

In addition to the value of patience being beneficial for performance, you need patience as well to guide your program design. Since agility work has a lag time, proper progression into more advanced drills should only be prescribed with the understanding that muscle may adapt faster than tendon, ligament, and cognitive ability – just the same way that strength will increase much faster than its ability to be transferred into speed or CODS.

It takes athletes time to adopt this newfound ability into agility technique because they already have built-in preferences of body lean, foot placement, stride adjustments, and many other factors that now need slight tweaking in order to maximize their new potential.

Just like a new hockey glove needs to get broken-in, you need time and practice to break-in your new ability.

Strength Types and Agility Transfer

If you look at the qualities of agility I provided above within the lists, you will notice that I divided strength into concentric, isometric, and eccentric contractions.

Concentric contractions represent the muscle shortening effect of a movement.

For example, when you are doing a biceps curl, you can see your biceps shorten and peak on the way up. This is the concentric phase of the movement.

Isometric contractions represent a muscle that is contracted but is neither lengthening nor shortening.

For example, just hold a biceps curl at the mid-way point (90-degrees) and keeping it there in an isometric contraction. The muscle is still creating and resisting force, but it is neither lengthening nor shortening.

Lastly, the eccentric muscle contraction represents the lengthening of a muscle during movement.

For example, the downward phase of a biceps curl. As you slowly control the bar on the way down, you can see the biceps move from a “peaked” contraction, to a more elongated (but still creating and resisting force) structure.

The reason why I included these separate contractions within the specifications above is because strength can be expressed and therefore measured during different muscular actions.

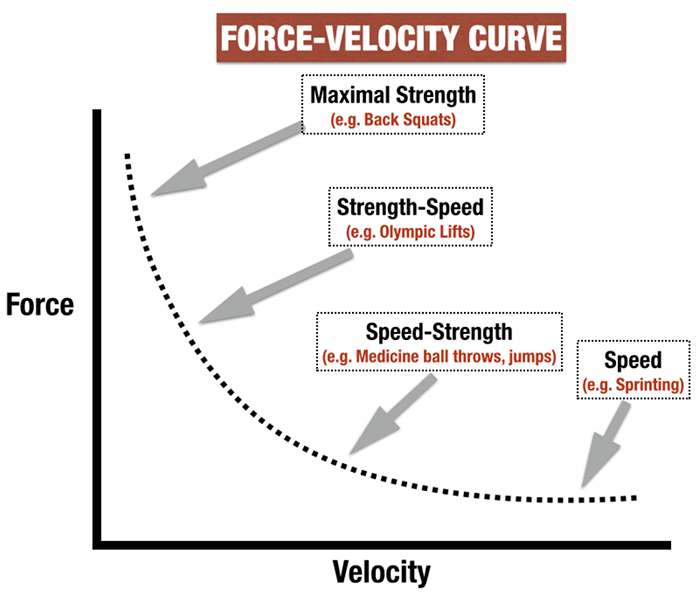

This expression and force capacity is commonly represented on the force-velocity curve of muscles as shown in the figure below.

Much of what is done in strength and conditioning program design and periodization structure is completely based off of this model

Depending on the individual genetic characteristics of the hockey athlete, how long they have been training at a high-level, what their athletic and training background is, and what particular phase of programming they are in right now – an athlete will have unique levels of eccentric, isometric, and concentric strength.

Each type of strength is used during a COD as the athlete brakes and decelerates (eccentric), transitions (isometric), and then accelerates in the new direction (concentric).

In most cases, coaches are so focused on only the concentric contraction of their training stimulus, but, it is not always necessarily the case that the athlete who has the most exceptional concentric strength is also going to have exceptional levels of isometric or eccentric strength; and as you know now, you’re going to need all three to effectively execute your reactive ability out on the ice.

This also means that anyone or multiple types of strength could be the “weak link in the chain” that is creating the limiting factor in an athlete’s agility development.

This also means an athlete’s limiting factor in agility could be masked if only concentric strength is used as a testing parameter for agility and/or athletic development.

I personally feel eccentric strength and deceleration are two topics that don’t get enough respect in today’s conversations surrounding hockey performance enhancement.

It is very certain to say that eccentric strength plays the largest role in a hockey athletes ability to brake rapidly – it is this exact strength and action that is required when changing direction at high velocities (“cutting”) or when changing directions at extreme angles that require a substantial amount of force first be absorbed before concentric contraction can occur.

Put shortly, agility performance is highly unique and is the accumulation of both physical and cognitive-perceptual abilities. A hockey athlete and coach who understand the strength and weaknesses of these factors will be able to find the largest window of opportunity to enhance agility performance.

You are only as agile as your weakest link, once you identify which link this is, the program design will write itself.

Technical Breakdown of Movement Mechanics

Breaking down technical efficiency in words and not in demonstration is a tall order, so I want to begin this section by articulating the importance of having a coach with an eye for detail and a high level of experience watching every move you do in the beginning.

You may already have perfect technique, in which case, your time would be better spent working on some of the other areas for agility development.

But, in most cases most of the time, many athletes have some bad habits – and then when they start training they start making those bad habits become a concrete foundation upon how they move in sport.

That by itself is a problem because if you don’t have technical efficiency it doesn’t really matter how great your other qualities are, you will always suffer.

Just like a big strong man who doesn’t know how to punch will never hit harder than a world class boxer even multiple weight classes below him; you will never have agility if you don’t know how to move properly.

A coach can help immensely in this area of your development.

Beyond this, I want to make it very clear that this section will be discussing the technical breakdown of your dryland agility training. I am not a hockey skills coach and I have never claimed to be, what I am though is a high-level strength and conditioning coach.

My job involves being in the gym and being on the track, so I intend to stay in my lane here and utilize the dryland techniques that I know transfer tremendously to on-ice agility development.

Agility (some call what I’m about to discuss, “quick feet” type of training) drills still involve a very strong element of linear and straightforward sprinting exercises at certain phases of the drill, much like you would see in a conditioning or speed drill.

For this reason, we still need to keep our running technique in mind and perhaps do an article on running technique alone in the future, but for now, let’s look at the techniques that are specific to agility and not just sprinting alone.

#1: Deceleration

Deceleration is exactly as it sounds, it is the act of slowing down an object that is already in motion/has momentum.

In the context of agility, although almost never discussed amongst professionals, provides a very natural and essential function of multi-directional movement since most athletes aren’t strong or powerful enough to “cut” on the spot, or turn on the dime.

This is where an athlete decelerates very quickly and maintains extremely high levels of acceleration that was created out of the “plant phase” they created when switching course and changing direction.

The ability to “cut” on the dime is the ultimate pinnacle of athletic agility and is primarily regulated by your strength and power output.

The objective of deceleration training is to decelerate only as much as you need to in order to re-accelerate in another direction. Read that sentence three more times.

One way you can gauge this (and thereby test it) is by observing an athlete and determining if they are over or under-decelerating during an agility drill.

If you’re under-decelerating, you’re not slowing down enough on your turns which lead to a delay in direction change.

If you’re over-decelerating, you’re slowing down too much (or even completely stopping) on your turns, which leads to a delay in direction change.

How do you identify if you are committing too much to either one of these errors?

For under-deceleration, the runner will either take too few stutter steps and move too fast when they change direction – this creates an obvious delay in movement.

If this is the case, the runner should take a couple of explosive stutter steps and move a bit slower. If this removes their delay (their time trial goes down in whatever drill you’re doing), they were under-decelerating and you removed the error.

For over-deceleration, the runner will take far too many stutter steps or move too slow before attempting to change their direction and re-accelerate.

If this is the case, the runner should take fewer stutter steps and trust themselves to move faster going into the turn. If this removes the delay, then the athlete was over-decelerating and you removed the error.

I know this is very tough to differentiate, and it is in person as well. This is why it’s good to have a trained eye around, but it’s also good to just do trial and error. You’re going to figure it out.

The goal is always to close the gap between shortening your deceleration phase but with keeping no delay on your turn. You should be looking for constant movement in and out of turns as much as possible.

The hockey athlete should literally look like they are maintaining speed during the direction change, the best athletes do this flawlessly both on the track and on the ice.

From an art of coaching perspective, I can tell you over-deceleration is normally just an awareness thing. Tell them they are slowing down too much so they can become mentally aware of it and fix it. But, under-deceleration is normally due to a lack in strength and power development. From experience, these should be your initial “go-to’s” for problem resolution.

#2: Body Angle

Body angle is one of the major keys to your success in being able to change direction and express maximal force in the most efficient way.

What you want to see your athlete have is a 45-degree body angle when exploding out of the plant phase, it is this angle that maximizes the gravitational support (as opposed to keeping an upright posture, which is only reserved for longer duration “top speed” efforts).

#3: Plant Phase Positioning

In any movement scenario, the outside plant foot should be “90-degrees” from where the body is going to go.

In biomechanical observation, this should happen naturally all the time if the hockey athlete has no mobility issues in the hips. But, often times hockey athletes do in fact have this issue, so it can be a real anchor that holds hockey players back in their performance.

If you want to explode to the right, you will plant your left foot down and face forward at a 90-degree angle from the direction you’re going (just think “skate bound” type of motion if you haven’t got what I’m saying yet).

This may seem like a basic technical cue for you, but, now you know at all times where your foot should be when going through agility drills. We do this because planting the foot in this manner not only creates maximally force outputs but it immediately prevents any unwanted pivoting during the transition.

Too many times hockey athletes don’t position their feet properly, or they rotate too much, or they rotate too little, and what they don’t know is that they are risking injury when they do any of these poor technical acts. Hockey coaches and hockey athletes just don’t realize how dangerous pivoting is on the knees and ankles.

Just remember, you should always be planting with your outside foot at a 90-degree angle from where you are directing yourself almost always.

Planting on the outside allows gravity to support your movement and you will be much better able to recruit the glutes and hamstrings that are much stronger and more powerful than trying to use your inside foot and therefore recruit your groin (adductors primarily).

And if all of that weren’t enough, planting the outside foot at a 90-degree angle also creates a more natural transition into the 45-degree body angle that’s required for maximum acceleration.

#4: Feet First, Body Later.

Sound like a weird cue for you or your hockey athletes?

Yeah, it kind of is, but it’s also true.

It is a lot easier to move your feet under your mass instead of moving your mass over your feet, especially when trying to change directions. This means you have to remain cognitively aware of keeping your feet and lower body in constant motion when switching directions rather than doing it all in one whole-body movement. Quick feet here.

#5: Hip Rotation

I have spent a tremendous amount of time studying the hips and why so many hockey athletes suffer from hip tightness and mobility issues. Some of my knowledge comes from what’s measurable within the data, other fractions of my knowledge come from what’s observable in practice, both are equally pivotal in hockey performance.

If your foot is in the right position (at 90-degrees) then the next step is to really open up those hips and use them to take your first step in the new direction. The hip turn really sets the stage and feeds the energy and explosiveness of what direction we are moving towards.

The hip is meant to rotate, so rotate it.

It contains some of the biggest and strongest musculature in the entire body, and it is entirely possible to use this musculature to our advantage in agility training.

Focus on turning your hips after the plant phase and you will be in a stronger and more powerful position to create maximal speed and agility.

#6: Total Body Positioning

Your total body positioning and stance is another “make or break” factor in agility and quickness. A solid athletic stance mostly just comes down to posture. You don’t want to be structurally imbalanced or positionally imbalanced in any way when attempting to change direction at high velocities.

Your weight should be balanced throughout your feet, you should be on the balls of your feet, and you’re going to want a slight bend in the knees with your hips back, back straight, and shoulders forward from a lateral perspective (think of what most people refer to as “athletic stance”).

From the front, your feet are shoulder width apart and you should look perfectly symmetrical – I should be able to take a picture of you and draw vertical lines from the front of your feet, through your kneecaps, through your pelvis, and up through your shoulders.

If you’re in this athletic stance, you’re ready to accelerate in any direction.

Technical Recap

Overall, technique is arguably the most important factor for agility because it doesn’t matter how well developed your body and mind is if you do not possess the technical skill to execute the movement.

Think of mental and physical capacity as your potentiators of agility, and technique as your ultimate expression of agility. These three (physical, mental, technical) are not to be seen as separate from one another, but rather extensions of one another. They all blend together in the human performance spectrum, but at the same time they act like a tripod.

A tripod has three legs, and the agility tripod has three legs.

Leg 1: Mental

Leg 2: Physical

Leg 3: Technical

What happens when you knock one of the legs out from under a tripod?

The whole stool falls down.

That’s exactly how agility works as well, you can have one or two of these and think you’re a complete athlete, it doesn’t work like that.

You might be a good athlete, or even a great athlete, but neither of those statements means that you’re going to reach your athletic potential. You need all three.

This section, although focused on dryland training, is one of the most important sections of this article. Dryland training translates directly to on-ice performance (if you do it properly that is), so the greater quality we can get from our dryland training means that we will gain a greater adaptation out on the ice.

Technique is one of these things at the top of the mountain and should never be overlooked. Dryland or not.

Testing Agility in Hockey Athletes

Agility is a trait that all hockey athletes want and a trait that all coaches are looking for, and even though it is an incredibly important trait, choosing both appropriate and meaningful testing method proves to be very difficult.

Coaches need to have the knowledge and experience to choose tests that include both the physical CODS aspect, as well as the perceptual-cognitive aspects of agility as well.

A test and/or testing methods need to incorporate both because the research is clear in that both have been shown to play equal parts within sports.

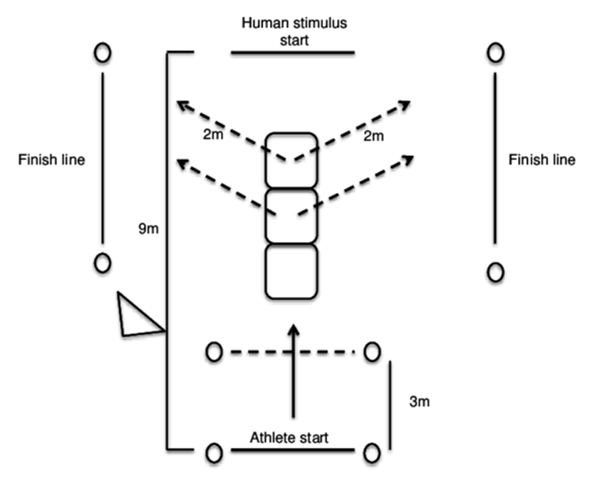

Originally, a test was created known as the Reactive Agility Test (RAT test) which allowed athletes to not only perform a rapid change of direction to display physical ability, but also respond to a stimulus on the screen. The athlete is required to assess the position of the image of an athlete on the screen and then change direction to the appropriate side.

Sine the original RAT, multiple researchers have tested multiple protocols with a variety of different stimulus methods that have included both video projects and human stimuli. The human stimulus has been shown to be most reliable during a RAT – which is great for us because coaches and athletes are able to set up this testing without any kind of high-tech equipment (which is my favorite, because who cares about a test when you need a $50K piece of equipment).

In the above sample test, when the athlete crosses the start timing gate line (the dotted line 3m in front of the start line) the human stimulus will move. The athlete changes direction either to the left or right in response to the direction the stimulus moves.

A high-speed camera is then used to assess the decision-making time from when the stimulus initiates movement until the athlete initiates movement toward the intended direction.

This is great stuff because you get a mental and physical breakdown of your athlete’s agility, but, you also gain quantifiable data through the high-speed camera. That camera will also pick up important things such as foot placement, angles, hip rotation, etc.

Utilizing CODS tests can be tricky and picking the right one for your athlete can be even trickier but let me provide you some framework here through a fundamental breakdown of the bests tests and which category they belong in for your assessment.

Change-Of-Direction Speed (CODS) Tests

- Traditional 5-0-5 (high-velocity)

- Modified 5-0-5 (low-velocity)

- Pro-agility (high and low-velocity)

- 10m shuttle (moderate to high-velocity)

Maneuverability

- T-test

- L-run

- AFL agility test

- Three-cone agility test

Reactive Agility Test (RAT)

- RAT in response to a light

- RAT in response to video

- RAT in response to a human stimulus

Although these tests have several direction changes, in most all cases within hockey, it is a single and decisive change of direction that is required to change the play and/or enhancement your position on the ice.

That’s why the above tests are broken into three categories:

- CODS tests that require either one or two high or low-velocity entry changes

- CODS tests that require three or more changes of direction with more curves than sharp changes of direction – and therefore more representative of maneuverability

- RAT tests that require a change of direction in response to stimuli

To make things more complicated for you (if they weren’t already), in order to properly test for agility, you need to try and be as narrow as possible as to the type of quality you are trying to test for.

Therefore, it must be demanding enough to differentiate performance between two different athletes in a clear way, but, also be short enough to where it doesn’t “muddy the waters” by being so long that it becomes impossible to determine which quality was used during the test to either improve or limit agility performance.

This is where you start to eliminate other tests that are more often used in athletics, such as the straight-line sprint.

Although a straight-line sprint is a part of CODS, it’s still important to minimize the amount of straight-line sprinting require in a test to ensure that the testing result is representative of an athlete’s ability to change direction, and not just about how fast they are in a straight line.

Athletes shouldn’t be able to “make up” for their lack of agility through their superior sprinting.

This is why I’m not including things like “shuttle runs” in my above tests, it leaves too much of an advantage for sprinters and not narrow enough of a test for CODS or perceptual-cognitive ability – especially since it’s also pre-determined and not reactive to stimuli.

It’s also very important to point out that multiple studies show a large transfer of training of both your absolute 1-Rep Max squat strength and your relative 1-Rep Max squat strength to your times on the 5-0-5.

Therefore, developing hockey athletes focused on agility must realize that strength is a major factor in CODS ability. This becomes particularly true in high-velocity drills and extreme angles of direction change (up to 180-degrees).

So, for the millionth time now, yes I am talking to you hockey parents, lifting weights will not make your athletes slower.

“Ok I get it Dan, this all sounds great. But, you can’t possibly expect me to go through all of those tests, which ones should I do?”

Hockey athletes are unique.

In most sports, a CODS test and a RAT test would have been enough because that alone would have measured high-velocity CODS and mental agility.

But, since hockey requires both of those things, plus it also requires more subtle changes of direction at high speeds (for example, skating fast up the ice from your end as a winger but then doing an easy cut to move closer to center ice) – a measure of maneuverability should be in there as well for completeness of testing parameters.

I would personally recommend going with these:

- 5-0-5 (CODS)

- L-run (maneuverability)

- RAT test in response to human stimulus

From my review of the literature and understanding of hockey performance, I feel those are the most reliable and valid measures that most accurately represent what a hockey athlete needs on the ice.

If you use these tests, you will have a phenomenal foundation to stand on in order to properly measure your athlete’s agility profile and having this data will provide you the “weak link in the chain” you needed to know about and work on in order to take agility to the next level.

Coaching Methods for Hockey Agility Training

Once you have conducted your basic hockey agility testing methods, this provides you very insightful information on both the “why” and “how” behind your future programming decisions.

Although I would want to point out for the sake of completeness that testing for agility all by itself isn’t wise and that you should be testing for all components of hockey performance in order to get a full picture of what is going to be the next big thing you do in order to progress.

If you don’t know what else to test in order to get the complete picture, I already answered all of these questions for you within the Hockey Assessment Manual I created this year, in it you will find an eBook and video to run you through exactly what you need to do in order to identify that “weak link in the chain” that is currently holding you back in your hockey performance.

You can check that out, or, it also comes completely free if you are on the Off-Season Domination plan.

But, since all of the other testing has crossover to agility but isn’t necessarily agility specific (like the ones I laid out above) – I won’t continue the conversation further here.

What I do want to get into is how you can progressively incorporate drills into your hockey program in order to maximize agility – but this has to be in alignment with what type of coaching cues I want you to have in your brain when doing these drills.

The thing is, knowledge of effective body position for force application will transfer in athletics only through the use of effective coaching cues in conjunction with the athlete’s own visual and kinaesthetic feedback.

This means, in most cases even the most elite of hockey athletes won’t just “get it” on their first shot, they need proper cueing from a good coach in order to imprint the proper agility coordination into a new habit.

Motor learning research in this area has shown that externally focused attention enhances CODS more than internally focused attention. Externally focused attention occurs when the hockey athlete targets their focus on their environment (such as the ground and/or a piece of equipment); whereas internally focused attention involves attention on the body parts themselves.

In a perfect world, you would use a blend of coaching cues that incorporated both external and internal – but the primary point I am trying to make here is that you can’t forget your external cues.

For example, the external coaching cue of “push the ground away from you” when starting a sprint or going into a cut more properly conveys to the athlete how to effectively drive hard into the ground and utilize a 45-degree angle while doing so.

But, you could create an effective blend of both internal and external cues by instructing the athlete to “push the ground away from them” (external) to start their sprint, but then insist that they “finish their drive” (internal) at the same time which leads to better extension of the leg and an overall more explosive start.

If all of this internal vs. external stuff sounds confusing to you, don’t worry, it’s complicated stuff and agility isn’t as simple as just running around some cones. Always remember:

“Hard on us, easy on the athletes”

They only need to here the cueing, you don’t ever have to tell them anything about ground reaction forces or angular velocity – nor should you.

But to keep things simple, here are some tips in the cueing world that are tried and proven:

- Identify cues that work with specific athletes in the gym if you’re already working with them in weightlifting and then use those cues out on the field as well. They already understand the cue, and this could help prevent the “lag time” in transfer that we discussed earlier

- Use simple cues, never be overly complicated. “Finish your drive”, “Push the ground away from you”, “Extend like a leap frog when you jump”, “Cushion the landing” – are all great examples of something simple and actionable. “I want you to press down with your foot at a 45-degree angle and contralaterally pump your upper arms while achieving triple extension at the knee/hips/ankles while maintaining a neutral spine” – is an idiotic tip that is more about you trying to appear smart in front of your athletes as opposed to actually help them

- Visual cues such as pointing at the center of their belly during agility drills will help athletes remember to keep their center of mass balanced during movement

- Provide athletes with a pretend scenario during their agility drill so they can learn to use movement patterns in a more realistic type of scenario. It’s no longer a “drill” – they are now breaking it out of their own end during a penalty kill. You can see how in these scenarios we start blended both the physical and mental aspects of agility without needing to resort to a “human stimulus” in order to do so

- When providing scenarios, use both offensive and defensive events instead of just one thing all the time (remember, let’s get both hemispheres of the brain working here)

Rehearsal vs. Reactive Agility

Rehearsed agility drills are exactly as they sound – rehearsed. Meaning, the drill is being performed in a pre-meditated and choreographed pattern. The athlete already knows exactly what they are supposed to be doing, where they need to go, what movements they need to perform, and where the endpoint is.

Rehearsal drills can be great because they teach the athlete proper technique, they build up physical preparedness, they build up confidence going into high-velocity cuts, and it allows them to really master movements that were previously foreign to them. When you combine all of this, you get an athlete who has programmed new motor habits into their movement.

And for us, it can be a great way to make sure our programming is actually working because rehearsed drills are easily measurable. Cone drills and suicide-type runs are good examples of rehearsal work.

The biggest takeaway here is that when you are performing rehearsal drills, you don’t need to make any decisions – you just do them.

Reactive on the other hand is the complete opposite, this is where a stimulus needs to come into play in order to bring decision-making back into the workout.

Reactive training is incredibly beneficial for your development as an agile hockey athlete. Many agility drills currently in existence fail to relate to a game situation through one major flaw; it is a completely predicted movement.

When you are executing a predetermined movement, it’s towing the line pretty dangerously between the idea of speed vs. agility.

If you already know what you’re doing, how is this true agility movement?

A predetermined pattern is exactly that, predetermined. Whereas for you to be agile in a game setting demands that your movement is predicated exclusively on your ability to respond to stimuli.

Live action hockey stimuli including:

- Where the puck is

- Where your teammates are

- Where the opposing team players are

- Where are you on the ice

- What plays can you make happen from here

- Is anybody open?

- Is anybody coming at me?

There are a multitude of things in your brain all flying in at the same time (funny how the mental game always makes its way back into the conversation doesn’t it?) that you have to be able to effectively and quickly respond to.

Hockey is chaos, so a little chaos in your agility work will go a long way.

Instead of moving in a perfectly predictable fashion all the time, try incorporating some reaction work that demands you respond to an unpredictable stimulus which is going to determine your route of movement.

Since agility is both mental and physical, reactive training can become an effective tool as your mind has to be on point and alert to ensure your body executes the correct movement (and therefore, becomes truly agile in a chaotic environment).

Agility is not just about direction change on the ice or on the ground, but how your brain performs the visual scanning, anticipation, pattern recognition, knowledge of the situation from past experiences, and reaction time before movement.

All of this stimulus occurs once direction change has been made where you have a new line of sight, and this chaos/reaction should all be viewed right in there with the physical characteristics of complete hockey agility.

This is where reactive training comes in and can be a great tool in addition to your already existing agility work, but now training both the mind and the body.

A couple of my favorite drills to use with my hockey athletes include:

Sprint and Chase

Two athletes pair up and they are separated from each other by 5-15 yds. They are both facing each other but the one in front is seated and the one in the back is in a 3-Point sprint stance.

How it works is the seated athlete is to get up, turn around, and sprint 5-15 yds, but, the moment he makes a move his partner can begin chasing him. The idea is for the seated athlete to be fast and agile enough to explode and turnaround from a seated position and beat his partner to the finish line.

Lateral Mirror Drill

Two athletes pair up and face each other, one is designated as the leader and the other the follower. Two cones are set up 5-10 yds apart and the leader is to move laterally back and forth as fast as he can while the follower has to react and follow him the best he can.

10-30 seconds of non-stop movement is followed up by 20-40 secs rest in between rounds.

4-Corner Point and Touch

Four cones are placed in a square, Partner A stands in the middle of the square while Partner B points to which cone Partner A has to sprint to, touch, and then return to center. This is done for 20 secs non-stop, with 40 secs rest, for 5-rounds. Each partner performs 5 rounds.

To wrap this section up, athletes who have never done reactive agility work would benefit greatly from incorporating it into their routine from time to time based on need/importance/periodization schedule.

In most cases most of the time, I like athletes performing this type of work immediately before their conditioning training.

We do it before as trying to be reactive/explosive after a workout would negatively affect the reaction time of the athletes and ultimately lower their performance for this specific task.

On the flip side, if this causes a little pre-fatigue before a conditioning session, that’s fine because they are performing conditioning work anyways which should be effectively training their body to continually create force production in a state of fatigue.

Having said all of this, in no way do I want you to feel that I am saying rehearsal exercises are bad, they are not. They are just a different tool that is more usefully used at a different time.

The reason why I am emphasizing reactive work is that I see a lot more athletes doing pylon drills than I do see athletes responding to any type of stimuli.

A combination of both in your programming is superior to either alone.

The Power of the Mind

You have already learned throughout this entire article how important the mind is towards agility and how it can truly be its own make or break quality.

We have the science-based technical impacts of the brain hemisphere activation and we also have the various impacts that both sport-specific stimuli and reactivity play on your ability to be agile.

Everything starts with the mind; the body is only a receiver of information and not a transmitter of information. Hockey is just as much mental as it is physical.

Most people assume the physical part, I mean that just makes sense, right?

Train the body for agility and your body will become more agile.

What many people seem to forget though is how important the mental aspect is behind what I would deem a more thorough and complete look at what agility truly is.

Agility demands you have a strong mental game, and when it comes to hockey this requires both mental agility, comfort, and confidence.

Let’s break down each one of these three components to further our knowledge of mindset and hockey.

Mental agility can be thought of as your ability to follow two conversations at once. You need to have the vision, attention span and focus to be able to read what’s in front of you in unpredictable environments.

A game setting is as unpredictable as it gets, in a matter of only a few seconds all the players on the ice will have changed their position and the puck can be far from where it originally was.

If you can’t foresee the actions of those around you and read the ice, agility can suffer.

Why?

Because a mental block is a physical block.

You may have all the physical components in the world but if you’re not “in the zone” it doesn’t matter what your body is capable of doing because your mind is making the wrong decisions.

Take the example of female gymnasts in the Olympics. You have a look at these girls and they are pretty much all identical height, identical muscle mass, identical flexibility, and identical builds.

So, what makes them different than one another on that day?

Their mind.

Whoever came the most mentally prepared is going to be the one who executes her routine most flawlessly. This plays out just the same in hockey.

Maybe the first and only reference ever towards hockey using female gymnasts?

Most likely.

But I know you can level with me here.

Everybody has had that game or had that workout where their mind just wasn’t there. Their body was physically capable of performing better, but it was being limited by your decreased mental performance.

So, what do hockey players need out there to make sure they have this mental agility?

They need the next two components, comfort and confidence.

You need these in order potentiate your maximum agility capability. Let’s look at another real-world example of how confidence and comfort can have a huge impact on your agility.

Let’s say this year you made it up to the next level in competition, you’re in the semi-pros now.

But with this progression, you also had to move away from your friends and family to another city, play on a team that you have never played with before, and you’re also traveling much more than you have ever been used to.

You’re probably not going to have the best hockey season this year. This is a lot of change and a lot to take on all by yourself.

But, you make it through the year playing pretty well, but not to the potential you know you are capable of… then next year/the next season rolls around.

Now that you have spent a ton of time here – you’re comfortable in your new city, you have a lot of new friends, you know and respect the coach now, you are used to your teammates and know how they play, and you’re also used to the traveling schedule.

You may not have actually changed at all physically, but your performance is going to increase drastically this year compared to your last year just because now you’re more comfortable and confident. This plays directly into your agility.

The more confident and comfortable you are out there in a game setting, the more agile you will appear regardless of your current physical fitness.

Conversely, no matter how physically prepared you are – you will never reach your potential without having your mind in the right place.

Until you’re mentally ready, you will never be truly physically prepared.

Warming Up to Maximize Agility

I’m sure many of you recall your gym class warm up, or, unfortunately maybe your hockey warm-ups. Let me guess:

Laps upon laps of some light jogging.

A random, non-sequenced collection of static stretches.

And we’ll finish it off with some jumping jacks for good measure.

This “traditional” warm-up style has been around for decades, and there have been plenty of advancements in science since then. Very few people question their current warm up, or perhaps maybe just under-value warm-ups as a tool for agility enhancement.

I must admit that I too was guilty of under-valuing warm-ups, that was until I dug into the research and started using them with my athletes and saw immediate increases in speed, agility, and jump height/distance.

The science behind warming up properly is incredibly extensive at this point, but what I want to do for you is break it down into four simple steps that you can take home and use immediately – and also talk briefly about why we are using these four tactics.

STEP 1: Active Flexibility Movements

Traditionally, most people would include static stretching as a part of their warm-up routine, but I have been very vocal in the past about how this is actually counter-productive towards hockey performance.

The biggest factor is the fact that as of now hundreds of studies have been done on measuring performance in 1 rep max, running speed, reaction time, isometric torque production, jumping, and throwing with most, but not all of them, report decreases in performance from a combination of both neurological and muscular factors.

It is also important to note that this performance decrease seems to have a linear relationship with how long you hold the static stretch. Meaning, the longer you hold it, the greater negative effect it can potentially have on your performance.

Here’s a quick breakdown on a meta-analysis performed in 2012 compiling 104 total studies on stretching performance:

-

- A very likely negative effect of performance from static stretching on explosive muscular contraction

- A likely negative effect on maximal strength

- A likely negative, although inconclusive effect on muscular power

In addition to the above, many of the studies deemed inconclusive have neutral performance effects, meaning no better or no worse.

In a game like hockey where everything is measured in inches and milliseconds, we need every single advantage we can get. Just as importantly, we need to eliminate any possible negative outcomes we can.

Where does that leave us?

Static stretching is to be kept in the post-workout, post-game window, because doing your static stretching work will reduce the neural drive of your Type ll muscle fibers and it should go without saying that hockey players need this to be functioning optimally in both their training and their games.

Active flexibility movements are far better placed in the warm-up window because they get you loose, they are better at raising core temperature, you can choose movements more relevant to hockey, they increase flexibility just as effectively as static stretching does, and they also provide all of these benefits without any reported downside effect on performance.

Active flexibility work is a real no-brainer here. Example active flexibility movements would include heel-to-butt runs, high knee runs, and walking toe touches.

STEP 2: Muscle Activation

In this step of the warm-up, we are basically “waking up” commonly weak muscle groups to ensure their participation in larger multi-joint movement patterns that will occur afterward (in the dynamic and plyometric work) to raise performance and prevent injury.

Also, your muscles have now just been stretched in the previous step so now is the ideal time to strengthen and contract target areas.

Here’s what we’re after:

- Stretch dominant and active muscle groups

- Strengthen and activate weaker less active groups

- Restore balance and alignment in the body before intensive training

- Reduce injury risk

- Improve overall movement coordination

Muscle activation exercises, when prescribed appropriately in a warm-up design, can stretch muscles that are overused and strengthen essential opposing muscle groups to drive proper balance.

For example, hockey players are notoriously tight in the hip flexors due to the nature of the biomechanics of playing hockey.

If you analyze the hips of hockey athletes, you will see that the hip flexors are tight and dominant – whereas the gluteal group (back of the hips) in normally both inhibited and weak. This process of overdeveloping one side and under-developing the other is what is known as reciprocal inhibition.

This type of imbalance isn’t the only one that exists in the hips, but it’s definitely the most common in hockey athletes.

With this type of thinking in mind, I always prescribe specific exercises for the hips and glutes to increase strength while simultaneously stretching the overactive and tight hip flexors. The beauty of this type of methodology is that we kill two birds with one stone.

Bird 1: Hips become more symmetrical.

Bird 2: Eliminate dysfunction in the hip.

(No birds were harmed in the making of this step)

The body’s functions are delicate, maintaining balance ensures there is no needs for other joints or musculature to over-compensate and cause issues. Some examples of exercises you would use in this phase include planks, reverse crunches, and hip thrusts.

STEP 3: Dynamic Movement Training

Here is where things start to get interesting.

At this stage of the warm up, the bodies internal activity is really starting to take off and both the muscles and the nervous system are almost ready to rock at full blast. Intensity, speed, specificity, and complexity are all being taken up a notch here.

In this phase you can expect:

- General and specific movement preparation

- Increases in energy production

- Increase nervous system activation

- You’re going to start breathing heavier and sweating now

- Increase psychological readiness

- Increase core temperature

- Increase joint lubrication

- Improve total body blood flow for exercise

Right now, fatigue is very low, and the body is primed for enhanced motor skills so utilizing highly technical general and specific movement patterns to improve athleticism are good-to-go here and is something that I do very often in practice.

All the kinks are being worked out, the cobwebs are off, we’re more flexible and ready to move more at this point.

Beyond this, now is the time to create and/or retrieve movements in the specific motor centers of the brain.

It’s just like performing some rehearsal sets of barbell squats can help you refine your technique if you haven’t squatted in a few weeks, or when you feel the need to go to the golfing range first before you actually play to “get the movement down” again.

The nervous system requires a brief session of practice with target movements in order to ensure it’s ready for high-intensity application in your workout. This is where the mind-body connection is truly made.

Example exercises during this phase would include A-skips, B-skips, carioca, and backpedaling.

STEP 4: Plyometrics

Now we are getting into some real work – I am expecting you to move very fast and explosive. Your level of effort is key at this stage of the warm-up. If you don’t have a high-intensity effort here, you will not gain the adaptations that would otherwise have improved your performance.

Plyometric movements are movements that take advantage of your stretch-shortening cycle (as discussed previously). This type of action increases the activity of our nerves and muscle tissue which results in a greater amount of total force production from our muscles.

This type of training is crucial for agility development and the proper progression of plyometrics will allow you to enhance both your acceleration and deceleration.

This notion of fast and extremely intense movement preceding our actual training has been researched, and the results were excellent.

A study in The Journal of Sports Science and Medicine analyzed the impact of plyometrics on agility training. The subjects who performed plyometric training in this experiment improved their agility performance by up to 10%, whereas the control group demonstrated very little improvement.

More research has been conducted in this area, but the main thing you need to take away here is that plyometrics produce power, and with this specific addition to your warm up, you will not only receive additional work capacity benefits, but you will also truly prime the body and nervous for performance. Once this is done, you’re 100% ready to rock.

Agility Workout Warm-Up

Heel-to-butt run x 10 yards

High knee run x 10 yards

Walking toe touch x 5 per side

Gliding calf stretch on wall x 10 pulses per side

Iron cross x 5/side

Plank 2 x 20 secs

Reverse crunches x 10

Single leg hip thrusts x 8/side

A-skips x 10 yards

B-skips x 10 yards

Build up sprint 2 x 20 yards

Carioca 2 x 10 yards

Box jumps 2 x 5

Broad jumps 2 x 5

Hockey Agility Drills and Workouts

Reactive Hockey Agility Drills

Pick one of these agility drills and add it to the start of one of your hockey conditioning workouts to become more agile on the ice!

Sprint and chase: Partner A seated 15 yds ahead of Partner B who is in three-point stance. The line is set 15 yds behind Partner A’s back. Each partner performs 5 rounds in each position.

Lateral mirror drill: 10 yd cone separation. Partner A is the leader and Partner B is the follower. 10-20 seconds of non-stop movement is followed up by 20-40 secs of rest in between rounds. Each partner is to perform 5 rounds in each role.

4-Corner point and touch: Four cones are placed in a square, Partner A stands in the middle of the square while Partner B points to which cone Partner A has to sprint to, touch, and then return to center. This is done for 20 secs non-stop, with 40 secs rest, for 5-rounds. Each partner performs 5 rounds.

You can watch the video demonstration of these drills here or below:

Deceleration Agility Drills

A: 3/6/9 Deceleration Suicides: 5 x 1 with 90 secs rest

B: Front Deceleration Off of Box: 10 x 1 45 secs rest

C: Lateral Deceleration Off of Box: 10 x 1/side 45 secs rest

D: Hurdle Hop + Iso Hold: 5 x 3 hurdles with 60 secs rest

E: Lateral Hurdle + Iso Hold: 5 x 3 hurdles/side with 60 secs rest

You can watch the video demonstration of these drills here or below:

Hip Mobility Routine to Increase your Agility

A: Seated Piriformis Stretch (20-30 secs/leg)

B: Seated Glute Stretch (20-30 secs/leg)

C: Rear Foot Elevated Hip Flexor Stretch (10-12 per rep)

D: Iron Cross (10-15 reps/side)

You can watch the video demonstration of this routine here or below:

Hockey Agility Workout with Incorporated Deceleration Work

A: 3/6/9 Deceleration suicides x 5 with 90 secs rest

B1: Partner banded resisted lateral shuffle 10 yds there and back = 1 rep (5 x 1 with 0 secs rest)

B2: Triple broad jump x 1 with 90 secs rest

C1: Lateral bounds x 3 in each direction = 1 rep (3 x 1 with 0 secs rest)

C2: Sprint 20 yds x 3 with 90 secs rest

You can watch the video demonstration of this workout here or below:

Hockey Agility Workout

A1: Reverse scoop toss: 6 x 1 with 0 secs rest

A2: 3-Way pushup: 6 x 2 with 45 secs rest

B: Double broad jump into 20 yd sprint + 20yd backpedal: 6 x 1 with 45 secs rest

C: 10/10/10 Partner Agility Reaction Drill: 4 x 1 with 60 secs rest

You can watch the video demonstration of this workout here or below:

Hockey Conditioning + Agility Workout

A: Split squat jump with MB throw: 8 x 1 with 30 secs rest

B: Reactive Agility lateral shuffle: 4 x 20 secs with 45 secs rest

C1: Lay down turn around sprints: 6 x 30 yds with 0 secs rest

C2: Reverse scoop toss: 6 x 1 with 60 secs rest

You can watch the video demonstration of this workout here or below:

Hockey Agility Training Conclusion

It was my intention with this article to completely break down agility and create a major learning experience for the hockey community, I hope I succeeded at proving that for you today.

The development of agility, CODS, and perceptual-cognitive skills require a highly layered approach to your training. A correct test or series of tests should be chosen to identify your current capacity and the results of the tests will inform you of where you should be focusing in your training.

CODS and perceptual-cognitive training must be targeted in a long-term periodized fashion to ensure you make continual progress and are not just “winging it” by choosing random agility exercises.

Then, within these training sessions for CODS and perceptual-cognitive skills, I would consider it excellent coaching practice to incorporate both internal and external cueing to hone the athlete’s technical ability as much as possible for their performance.

Rehearsal work should be mastered before moving into reactive work, and agility training is something that is safe for hockey players of all ages.

Get out there, be smart, and have fun.

If you follow these guidelines, I promise you will create massive differences in your ability to be agile out on the ice.

Now if you’re ready to start training I highly recommend signing up for one of our Hockey Training Programs, which apply a lot of the agility training techniques talked about in this hockey agility article to help you become a better hockey player!