When it comes to assessing a hockey player’s skating, we typically just label them as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ skater. We note how a player is fast or slow, quick or lumbering, or how they have good or poor edge and footwork. Some players can legitimately buzz around the ice with poor form, and others can have great form and not be the fastest skaters.

But what actually constitutes a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ skater? What technical factors enhance or mitigate particular areas of a player’s skating proficiency?

I’m going to break down what makes a good hockey skater, starting with the most important component: the lower body.

Legs Feed the Wolf

Why is lower body structure so important in skating? As Herb Brooks would say:

It’s important to look at body composition in hockey skating from a ground-up perspective. The lower body makes or breaks the efficacy and efficiency of a skater altogether. How a player is taught (or not) to structure their lower body while skating during their peak development years can either set them up for success or hold their game back for years as they embark on the cumbersome journey of un-learning the habits they spent years improperly ingraining. That’s why becoming educated on proper mechanics at an early age is so vital to long-term development in hockey.

Before I dive into specifics, let’s first start by splitting the lower body into two segments to make it easier to analyze:

- Stance Leg

- Push Leg

Your stance leg is the front leg during your skating stride; the one that ‘grabs’ ice and is responsible for the onset of your push motion. Your push leg is just that: the leg responsible pushing and propelling you forwards along the ice. While both must work in unison to generate effective lower body mechanics, for the purposes of analyzing a player’s stride, it’s easiest to start by examining each leg separately. Just something to keep in mind as we move along this article and things get technical.

So without further ado, let’s get right into it.

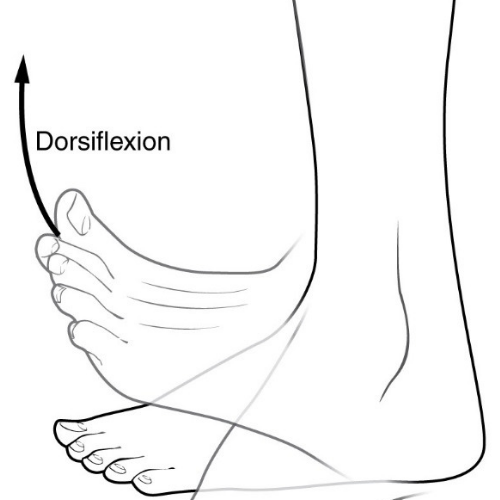

First and foremost, the ankle represents the single most important component of skating proficiency. Properly engaging your ankles in hockey skating involves ankle flexion, or dorsiflexion. Dorsiflexion is the act of flexing the toes up towards the shin bone:

Skaters with proper dorsiflexion at the base of their skating stride are able to generate a positive shin angle (a relative angle from the foot to shin that is less than 90 degrees). Players who can properly flex the ankle and generate a positive shin angle will increase their dynamism and athleticism in all aspects of skating and will be able to maximize control, power, and speed to a much greater extent than those who cannot.

Players without proper dorsiflexion while skating will struggle in just about every aspect of skating thereafter. Hockey players who can’t generate a positive shin angle won’t generate as much power, won’t be as explosive, and won’t be able to shift their weight or turn as proficiently as skaters who do have it.

It goes without saying, the ankle is backbone of sound lower body structure.

Tip: If your player is struggling to create a proper shin angle while skating, encourage them to take their laces down an eyelet to see if that helps, but more importantly work on their ankle mobility.

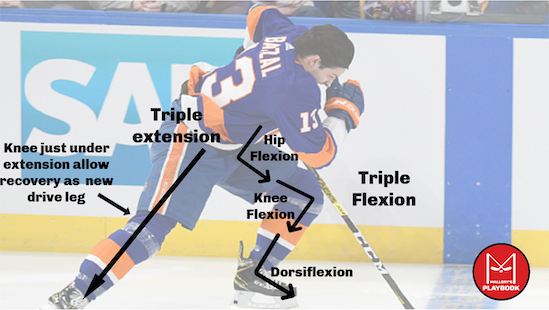

From a side profile, sound lower body structure in skating can be grouped into two main functions: triple extension and flexion.

Triple flexion involves the drive leg: hip flexion, knee flexion and ankle flexion (dorsiflexion) combine to create the triple flexion structure.

Triple extension involves the push leg: hip extension, knee extension, and ankle extension (plantar flexion).

The concepts are shown in the diagram below:

*Important: Knee extension on push leg should be just under full extension. We do not want to lock our rear knee out; the slight bend that remains in Barzal’s push leg knee is what allows him to recover his push leg as his next stance leg more quickly.

Barzal is showing perfect triple flexion through his drive leg (hip + knee + ankle) and triple extension through his rear leg (hip + knee + ankle), capped off by a ‘flick’ of his heel through each push to maximize the kinetic energy he’s generated through his stride.

And in motion:

Barzal has mastered his lower body structure, and it allows him to maximize the efficacy and efficiency of every stride he takes. When it all comes together, it’s beautiful to watch.

So, that covers the side profile of forward skating mechanics. But what about the frontal view?

In order to develop a proficient lower body in hockey skating, it’s vital we understand the mechanics that operate from our frontal plane as well.

From a frontal perspective, there are several important mechanical factors to consider along the lower body. The first and foremost consideration that makes or breaks a skater’s mechanics along the frontal plane is how they rotate their hips. Effective lower body structure in skating involves a calculated combination of internal and external hip rotation, and a disproportionate reliance on one over the other can lead to long-term mechanical quirks that are incredibly difficult to resolve at a later age.

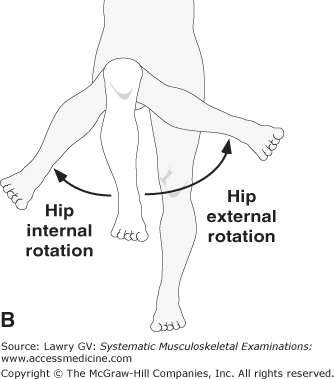

Before we apply hip rotation to skating, let’s define what it is in general.

External hip rotation involves the rotating of the leg away from the body. Internal hip rotation involves the twisting of the thigh inward from the hip joint.

The concept is illustrated in the diagram below:

The proper implementation of internal and external hip rotation is vitally important when it comes to developing sound lower body structure in hockey skating.

External rotation should occur in forward skating in the stance leg before the push begins. Internal rotation of the hip should engage through the pushing motion until full extension, as well as during the recovery of the push leg to become the new stance leg.

A common skating ailment in young players is having too much internal hip rotation. Skaters that utilize internal rotation too much will have the ‘knocked knee’ skating style you see so often. To truly generate power and velocity in our forward stride, we want to properly engage external rotation through our stance leg to get that ‘bow-legged’ look you see from great linear skaters like Morgan Rielly, Mathew Barzal or Connor McDavid.

In a twitter thread I wrote, I broke down how top 2021 NHL Draft-eligible defence prospect Brandt Clark struggles with linear skating from this very issue:

Clarke’s skating deficiencies in his lower body are rooted in his hips.

— Josh Mallory (@JMallory9) May 5, 2021

His ‘knocked knee’ style linear skating comes from severe internal hip rotation.

Compare to great linear skaters like Heiskanen & Rielly who activate external hip rotation in stance leg at onset of push https://t.co/nkxlq1ogWw pic.twitter.com/6RLidGhYPJ

Need IR during push leg recovery, but at onset of push from stance leg, the hip needs to enter ER with the knee pushing out (following ER from hip) and generate that ‘bow legged’ style we see from Barzal, McDavid & Kaprizov pic.twitter.com/HASI0m05RB

— Josh Mallory (@JMallory9) May 5, 2021

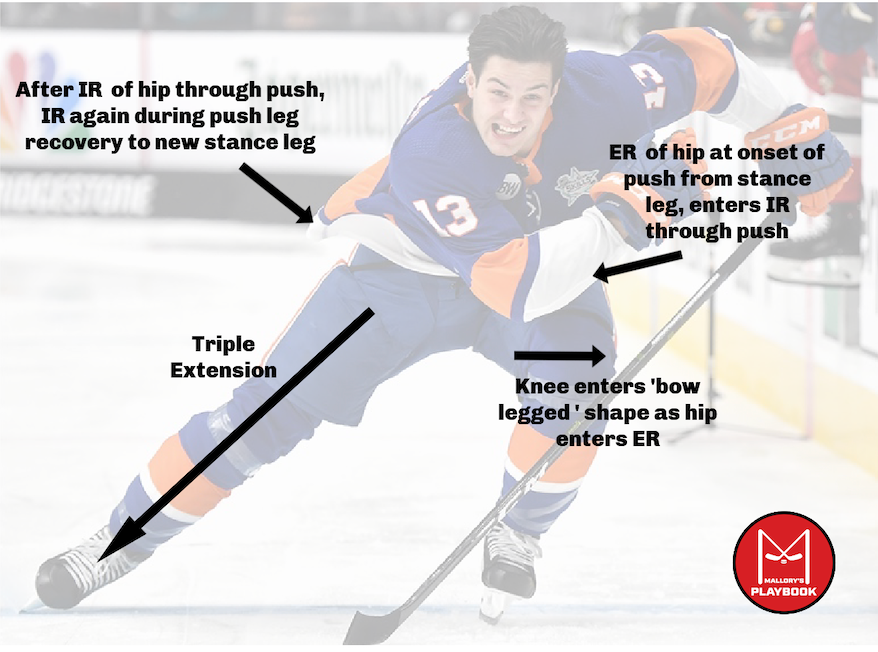

Now, I’ve brought it all together in the diagram below.

In Barzal’s stance leg, his hip is externally rotated and abducted which is what causes the knee to push out and create the bow-legged look. He then pushes through until his hip is fully extended (and abducted) in our triple extension form.

Then, once the push leg is set to recover and become the next stance leg, the hip should internally rotate and adduct to bring the push leg through and become the next stance leg, which again rotates externally and abducts at the onset of and through our push:

Below we can see it in motion from Connor McDavid:

- Hip rotates externally in stance leg at onset of push, abducts and extends through push

- Hip rotates internally and adducts through recovery

Now, we’ve covered linear skating, but what about crossovers?

Well, that’s where things start to get a little trickier.

When it comes to crossovers, we want to make sure we first understand the physics behind circular motion. Circular motion is simply the movement of an object along the circumference of a circle. The three main determinants in circular motion are speed, acceleration and force.

In order to maximize all three as well as minimize our wasted distance around the circumference of our circular path during crossovers, there are several mechanical keys we need to understand:

- We want our legs working underneath of our outside hip

- We want to push off our edges first and cross the leg over after

- We want to drive the push leg over the toecap of the stance leg

- Head, shoulders and torso should be stacked over the skater’s centre of gravity

- We want to achieve an angle on our edges (and thus the rest of our body) of about 45 degrees relative to the ice

- Keep shoulders and upper body neutral (no extra movement) and let our legs do the work

- Triple flexion through stance leg and triple extension through push leg (toe flick through push leg especially important)

For our first video example, a slow-mo of Connor McDavid:

And now, in full speed from Alex Formenton:

There’s a bit more going on during the crossover than linear skating, but it’s a vital movement to master the mechanics of to ensure sound lower body form through developmental years. Again, lackluster mechanics that aren’t corrected during key development years can hinder players for the rest of their playing career. Skating is the most important component of hockey to learn properly.

This piece has hopefully helped you better understand hockey skating’s most important substructure: lower body mechanics. Stay tuned for future pieces on the various additional elements of skating mechanics!

Are You Serious About Becoming A Faster Skater?

Now that you understand a bit more about the mechanics of the lower body, it’s time to prepare your body to be able to replicate those mechanics with power and speed.

Our Skills Accelerator AC3-System™ will provide you with customized year-round hockey training to transform you into the most explosive skater on the ice – allowing you to burn by opponents at will!

If you’re ready to make the jump to the next level and start working on building McDavid-like speed, get signed up for the Skills Accelerator AC3-System™ today!

About The Author

Josh Mallory is the Video Coach and Hockey Operations Coordinator with the Edmonton Oil Kings in the WHL. He is a current Masters candidate in Applied Health Sciences (Sport Management) at Brock University.