In this article, I am going to save you many hours of wasted time in your off-ice hockey training by breaking down and analyzing one of the most useless exercises that I see so many hockey players perform on a weekly basis.

That is…

Squatting on an unstable surface.

This can be a BOSU ball, balance board, or sometimes even a stability ball.

“Balance training” is something that has become incredibly popular throughout the entire hockey training industry, but most players do it incorrectly and see no transfer of improvement to an on-ice setting.

Even though many hockey coaches, trainers, or parents say “balance training”, they are really trying to accomplish is something more accurately described in sports science as proprioception.

Proprioception represents how the body reads information from various body parts/limbs in motion, as well as what’s going on in the environment around your body.

Think of it simply as knowing where your body is in space as well as the physical relationship it has with the environment around you.

This information is known as “proprioceptive feedback” and it is the language that your nervous system uses to figure out what is happening with your body and what move it should make next to accomplish whatever task you’re trying to complete.

Although this sounds fairly straightforward and that commonsense would dictate that an improvement in proprioception would result in an improvement in balance and therefore an improvement in hockey performance…

It doesn’t work out that way when you forget to apply the principles of training program design and get your programming priorities so out of whack that you actually hurt hockey performance development rather than support it with your training methods.

Why More Balance Training Isn’t A Good Thing

Balancing on a stability ball or BOSU ball while squatting is described by hockey trainers to produce more proprioceptive feedback than barbell exercises do.

Their logic goes along the lines of:

“Squatting on an unstable surface must be better for balance because more proprioception equals better balance!”

If you don’t stop and think about it you just might fall for that trick, but, deeper thought and research would tell us that more is not better in this department.

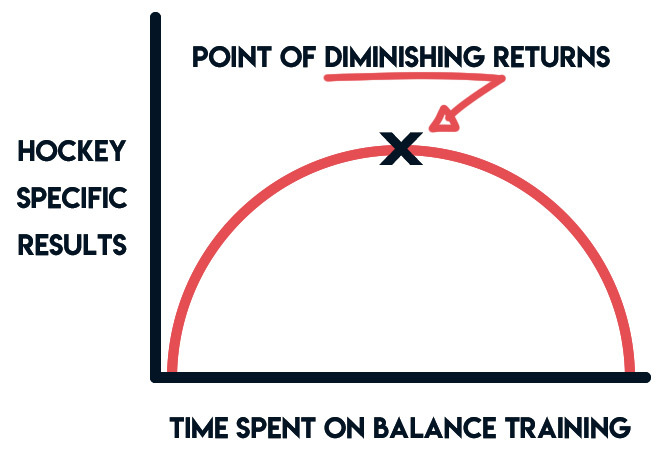

Meaning, there is a point of diminishing returns when it comes to these ideologies.

In the same way that hockey players don’t need to be as strong as powerlifters to become the best, they also don’t need to balance like gymnasts to be the best either.

I’m not saying all proprioceptive work is bad because it’s not.

But, like anything in strength and conditioning, the magic is always found in the application of the tool – and not the tool itself.

For example, a seated hamstring curl uses a fixed seated position and a fixed movement pattern that you are guided through by a machine where you don’t need to stabilize or balance anything — there’s certainly not a whole lot of proprioceptive feedback here.

All you get essentially is:

- Hamstring curl down

- Machine moves in a half-circle downwards

- Finish pressing down

- Machine moves back up in a half-circle

Not so complicated from a proprioceptive/coordination perspective, to say the least.

On the other hand, you could perform a lateral reaching lunge with dumbbells. This will require coordination through some major muscle systems in your body (hips, core, hamstrings, quadriceps, posterior chain, etc) and use these related muscle group in a way that is more consistent with the skating motion (for example, teaching the coordination of the hamstring to extend the hips while simultaneously controlling knee flexion).

This is much more complicated for the nervous system to grasp and demonstrates very clearly that the seated hamstring curl is less proprioceptively challenging than the lateral reaching lunge with dumbbells, and therefore could easily be argued that it is more functional of an exercise selection for hockey performance.

The hamstring curl machine stabilizes all movement which immediately reduces the proprioceptive feedback demand from your body (your body won’t need to calculate where you are in space or what’s happening in your environment if you’re just sitting there going through a fixed movement) in comparison to the reaching lateral lunge that is not stabilized by anything except your own muscular forces.

Not surprisingly, this is where the seed of “unstable surface training” comes from.

The lateral reaching lunge was not stabilized, and therefore demanded more proprioceptive feedback which made the movement more functional for sports performance.

Riding on examples like the above comparison between the seated leg curl and reaching lunges, some trainers a couple of decades ago thought that it would be a good idea to make it even less stable by throwing you on a BOSU ball or stability ball to demand even more proprioceptive feedback.

That theory sounds alright on paper, right?

Make exercises less stable to force more proprioceptive feedback and therefore “get more out of the exercise”

That is very easy to sell to a demographic who plays their sport on ice, but it is a far cry away from optimal programming for hockey players.

This is where the point of diminishing returns comes in…

Just because a high amount of neural information (proprioception) is being utilized during a movement, it does not mean that the information is meaningful.

The neural language your body is utilizing must have some degree of transfer/specific carryover to an on-ice game setting, if it doesn’t, you’re just learning how to do circus tricks and not learning how to become a better hockey player.

Using this same logic, we should be doing our cardio interval sets on a unicycle for “better results” because more proprioception would be required.

We both know that is a crazy statement, yet, it follows the exact same logic these people are trying to sell you when they make you squat on a stability ball or stickhandle on a wobble board.

Hockey doesn’t work like this and in no way, shape, or form doesn’t that represent the forces or environments that you will be exposed to in a game setting.

More proprioception does not mean more results.

And, in most cases, it actually means you will get fewer results since you’re spending more time on things that go beyond the point of diminishing returns rather than investing your time in more valuable areas for improving hockey performance.

Don’t These Exercises Work The Stabilizers Though? Isn’t That Important For Balance?

You would think so, but, when we apply unstable surface training for the purpose of improving hockey performance we run into a large number of issues that contradict what we know about improving functional outputs in athletes.

To start, it’s important to note that the “stabilizers” are not a distinct muscle group, and are incredibly different for each exercise.

This means it becomes very hard to logically program the “stabilizers” into a well thought out periodization strategy.

Moreover, most of the people who are proponents for this type of training couldn’t even tell you which muscles are being hit or what the stabilizing muscles even are.

How can you effectively program logical and measured progressions for your hockey player when you don’t know the muscle fiber type distribution, muscle insertion/origin points, pennation angles, biomechanics, or optimal exercises for stimulation?

It’s preposterous, I’m supposed to believe you are providing me an advanced training method, yet, you don’t know the anatomy behind the muscles we’re training or how we are going to progressively overload them over time to get better and better results?

That’s madness to me.

Not to mention, almost all “stabilizing” exercises are well below the volumes, intensities, and relative intensities required to promote ongoing strength, hypertrophy, and power development in advanced athletes.

What you’re really getting here is extra fatigue within the stabilizers and no way in which you can measure the optimal training frequency you should be applying on a week to week basis for maximal progress.

Furthermore, the stabilizing muscles involved in one movement are in fact a prime movement for something else.

If you knew what stabilizers you were targeting, wouldn’t you want them fresh for their own training so that they could be the prime mover of their exercises and therefore you could create a greater stimulus for progress within that set of musculature?

For example, your medial delts would be the prime upper body stabilizers when performing BOSU ball push-ups, but, wouldn’t it be more logical to want them fresh for your shoulder specific exercises so you can apply a much greater (and properly measured) volume, intensity, and frequency?

Pre-fatiguing a muscle group and reducing the quality of its own specific training for the purpose of gaining unnecessary proprioceptive feedback sounds highly illogical.

You Can’t Just Work The Big Muscles Though!

I never said that, and if you were involved in the programs here at Hockey Training you would know that I don’t take that stance.

However, I think it’s comical how people discuss “the small stabilizers” when in fact the large muscle groups are the most impactful stabilizing muscles on our entire body.

There’s a reason they’re large!

Our lats, erector spinae, chest, glutes, quads, hamstrings, abdominals (and many others) are all massive muscle groups for a reason—they stabilize our movement in the areas that drive the most force for athletic performance.

Yet for some odd reason, pseudo-advanced trainers are sacrificing the growth and strength of the muscles that impact our performance and injury prevention the most while simultaneously creating a training plan that focuses on much smaller muscle groups that they don’t even know the names of.

Big movements create big results.

Does this mean we shouldn’t train the smaller muscles?

Of course not. They have their time and place.

But, to create a program that minimizes the stimulation we can place on the most impactful muscle groups for hockey performance just doesn’t seem logical and doesn’t even come close to following the principles of program design.

My Trainer Told Me I Could Get Big, Strong, And Fast When Training On This Equipment And Train Balance At The Same Time, Is This True?

Not exactly.

Being on an unstable surface, you sacrifice speed of movement due to the challenges of balance — and since we know you need to move at a minimum of 90% of your max velocity to effectively train explosive power and speed we know for sure you aren’t getting faster by training on this equipment.

If you train slowly you will move slow.

You can’t think that slowly squatting on a stability ball will ever give you the explosive power you need for first step quickness out on the ice.

But, going hand in hand with the challenges of balance you also sacrifice how much weight you can use in a given movement.

The added load in the form of dumbbells or barbells on an unstable surface is a marginal fraction of what you could otherwise use on solid ground.

You can go way heavier with the support and stability of the ground in comparison to doing the same movement on a piece of instability equipment.

This means you have to go lighter, and since you’re going lighter you are also sacrificing your strength and muscle mass gains.

When you’re sacrificing strength development you are sacrificing so many things related to hockey performance I couldn’t even go over it within this article.

Shot power, explosive speed, acceleration, agility, conditioning, staying strong on the puck, injury prevention, among many other hockey performance factors all become decreased when you sacrifice strength development.

The most ironic thing here is that hockey players are utilizing a piece of equipment to become bigger, faster, and stronger — and yet this exact same piece of equipment is preventing them from doing all three of those things.

I Saw My Favorite NHL Player Do This Though, So It Must Be Good!

I understand my viewpoint on this topic can be shattering for some, especially if you have spent a lot of time or money doing these types of activities.

I’ve voiced my opinion on this topic in various videos and live events, and as a last chance effort someone usually shouts out the argument:

“Well, it works for (**insert random NHL player doing one exercise, once, on YouTube using equipment he is getting paid and sponsored by**) so it must be good! You’re not in the NHL Coach Garner, so you don’t know what you’re talking about!”

To begin with, I don’t know how this is even a rational argument.

It says absolutely nothing about how a muscle functions, how a muscle is stimulated, how a muscle adapts, and what key factors drive hockey performance.

First off, in many cases, these athletes are good in spite of what they do, and not because of what they do.

Just because an athlete does an exercise or certain training program it doesn’t mean they couldn’t be even better if they trained on a program that was well-grounded in sports science.

Beyond this, the “it works for him” argument doesn’t make sense when arguing for something that works directly against hockey performance in many ways.

To support this unstable training methodology, you have to openly look away from many well-developed arguments that go against your approach.

Put another way, to make this type of training your mainstay for the majority of your exercises, you would go through the scientific literature and find a few great studies to support your point. But, along the way, you would find a thousand more that didn’t support your point.

You’re not a special snowflake, the principles of training program design are principles for a reason…

THEY WORK FOR EVERYBODY.

Why anyone would dismiss the training principles or the facts we know about muscle physiology because they saw a video of an NHL player standing on a piece of equipment he is getting paid to promote is completely beyond me.

Deconstructing The Problem To Create A Better Training Future For Hockey Players

I think a lot of the misapplication of hockey training program design doesn’t come from a bad place of people just wanting to make money or spread bad information.

Instead, I think the problems lie behind a misunderstanding of balance and stability.

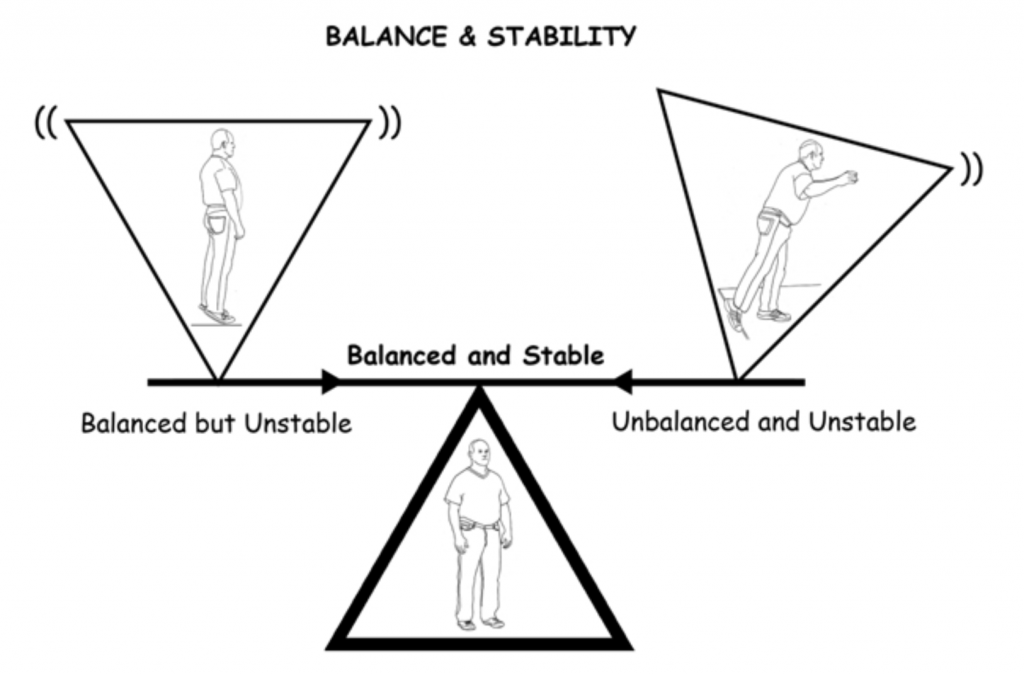

Balance training should never be mistaken for stability training, and yet I see these two terms utilized interchangeably on a regular basis.

Balance means that stability is produced by the even distribution of weight on each side of the vertical axis.

In action, this means to bring about a state of equilibrium (a state of balance between opposing forces).

Stability is the quality, state, or degree of being stable, as in the following:

- The strength to stand or endure (e.g. Rigidness)

- The property of a body that causes it when being acted upon by other forces to develop its own forces to restore the original condition (e.g. Stand your ground while being pushed)

- The ability to resist forces tending to cause motion or change of motion (e.g. being able to come to a clean stop and not have your momentum continue to move you forward on the ice)

- The ability to develop forces that restore the original condition as soon as possible after being taken away from the original condition (being able to return to a strong base of support on the ice and/or ground after being pushed or body checked out of the way)

Basically, balance is you manipulating opposing forces to create a stable state over a base of support – whereas stability is the control of unwanted motion to restore or maintain a position.

Think about this now…

What would have more transfer to hockey performance?

“Balancing” on an object, or creating strong “stability” in an athlete so that they are never taken off balance in the first place – and even when they are, they have the physical qualities to return to their original condition as fast as possible.

Things start becoming much clearer when we break them down, don’t they?

Out of the above two options, of course you’re going to choose stability.

Not just because it makes more sense functionally, but also due to environmental factors.

The ice never moves, it is a stable environment.

The ice is stable, it is never wobbling up and down forcing you to balance on it. It is forever stable, if any instability occurs, it would be because you are unstable and not the ice.

Yet, balancing on a wobble board or BOSU ball would indicate that you are playing on an unstable surface which just simply isn’t true.

Thus, stability training is incredibly more beneficial for hockey athletes both functionally and environmentally in comparison to balance training.

Balancing requires the transfer of low forces to maintain an equal state, whereas stability requires the transfer of high forces to create rigidity.

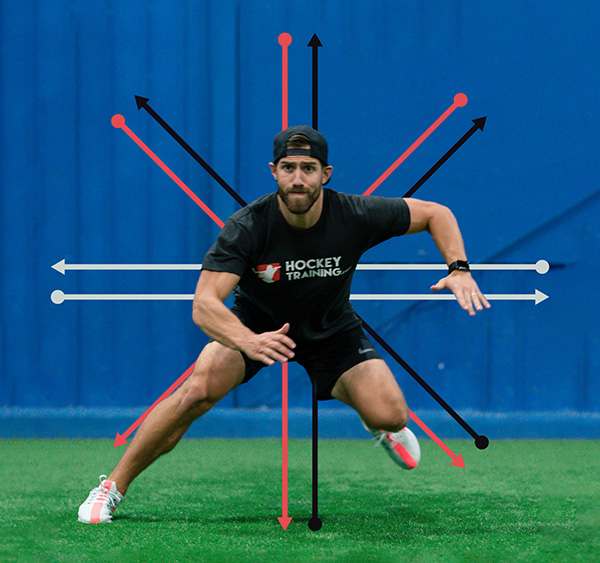

If you will recall from above, hockey players need to transfer high levels of forces from the ground up to create a sport-specific result, you can’t do this with balance training because it slows down both the load and speed of your movement patterns (not to mention, creates an environment your feet will never be exposed to in an on-ice setting).

Why Stability Training Is More Functional For Hockey Performance

As you can clearly see below, triangles allow me to drive this point home to you in a very simple to understand manner.

The stable triangle (or, stable hockey player) can withstand any force driven through its system; it is both strong and balanced.

The balanced triangle, on the other hand, can’t take any force unless you apply it perfectly on a vertical axis (think about it like applying pressure to an egg, it is only strong on the top and bottom).

If you think of a hockey player like a triangle that responds to high levels of multidirectional loading – then you must train it on its base and not on its point.

When the triangle is balancing on its point, you simply cannot apply enough load to create any significant training stimulus to occur.

The weight you would need to use to train on the tip of the triangle would be much lower than your actual strength capacity – and therefore not create a stimulus for any adaptation to occur.

A stable athlete will always be able to produce more force at higher velocities.

There is nothing for you to do from an unstable position (e.g. stand on one leg on a BOSU ball) except stand there, balance, and create non-important proprioceptive information that your nervous system will never need out on the ice.

You aren’t training to be a gymnast, you’re training to be a hockey player.

Hockey athletes cannot transfer high levels of force or maintain their position in the face of hard physical contact from a narrow or small base of support; you would be left completely at the mercy of the physical forces in your environment (e.g. getting easily knocked off the puck out on the ice).

This is why the athlete who does barbell back squats with 300lbs will always bully the athlete who does BOSU ball squats with 50lbs every single time they go after a loose puck.

Real balance training for hockey must concentrate on creating stability so that proper athletic positions can be maintained and forces can be transferred through the kinetic chain with maximum power output.

This comes from high-level resistance training and a thoughtful periodization strategy that prioritizes the right things at the right time.

Strength training is stability, and stability is balance done correctly.

Not to mention, strength is what allows us to express our skill more efficiently — and the combination of skill and strength is what takes care of the balance for us.

Think about it, do you ever “lose balance” out on the ice unless someone physically bodychecks you?

No, you don’t.

When you are skating you aren’t even thinking about balancing because your balance isn’t a limiting factor towards your speed.

You have to remember that an object in motion plays under different physical laws than an object that is still.

We see examples of this from all areas of life and yet people consistently never apply it to the sport of hockey.

Do you think he is balancing every single rotation of the basketball? Or did the strength of his initial spin allow momentum to take care of the balancing?

Do you think he is using an inhuman amount of strength to stay balanced on this turn? Or do you think the velocity at which he entered the turn allowed momentum to take care of the balance for him?

Do you think that he is focusing exclusively on balancing on his surfboard? Or do you think the momentum of the wave he is riding is taking care of the balance for him?

All of the above are very clear examples that strength plus skill takes care of the balance for us.

Strength gives us the acceleration we need to build momentum and allow the laws of physics to take care of the balance for us.

Think about all three pictures if they were still…

A ball is very hard to balance on your finger if you haven’t spun it yet.

A motorcycle is impossible to balance at that angle if you aren’t moving fast.

A surfboard is very hard to stand on in a pool yet you can glide leisurely when being pushed by a wave.

Now apply this to hockey and let me ask you the same question again…

Do you ever feel unbalanced when you’re skating out on the ice?

No, you don’t. Because the force you’re applying to your skating stride in combination with the technical skating skills you have on the ice takes care of the balancing for you.

The force you’re applying to your skating stride in combination with the technical skating skills you have on the ice takes care of the balancing for you.

So the real question is, if you want to have optimal balance, how can you produce the forces required to build the fastest acceleration/momentum?

You need strength, and strength only ever comes from stability training. Not balance training.

Something I always say to the coaches who want to learn hockey training program design from me is:

Don’t train a picture, train a video!

What I mean when I say this is that you should never look at a picture and think that if you mimic it you are doing hockey specific training.

This is wrong, you need to understand what happens before and after that picture was taken to truly understand what forces are being applied from the body and from the environment that allowed that picture to even happen in the first place.

If you were to train “a picture”, you would want the above motorcyclist to be the strongest man on the plant — but when you understand “the video” you realize that it isn’t necessary at all for him to have incredible total body strength because the laws of physics are doing a lot of the work for him.

Train the video, not the picture. Kevin isn’t using balance in this position, instead, he is absorbing and transferring forces through strength, stability, and technique.

Is There Ever A Point To Using Unstable Fitness Equipment?

In some cases, some instability can be desirable.

For example, I like to do about 1-2 weeks of ankle stability training using unstable fitness equipment with my athletes immediately after the in-season during the Regeneration Phase to strengthen those muscles (which are the two divisions of the peroneals and the tibialis) because they tend to get weakened by being locked in a skate boot for the past 6-months or so.

However, being on an unstable surface isn’t a very effective way to strengthen the ankle, and that’s why you don’t see it much in my programming.

If you’re standing on an unstable surface, your ankle joint isn’t changing position very much at all, and worse you’re not loading the ankle with any tangible velocity, acceleration, force, or anything that it would get exposed to during a hockey game.

This means the exercise makes you really good at maintaining a stable ankle in a fixed position (e.g. balancing with one foot on a BOSU ball or holding a deep squat position on a stability ball), but doesn’t really train you to create stability outside of this range of motion, absorb acceleration or create acceleration, or become stable in any position outside of this static stance.

For the most part, the main value in this static type of training is for individuals who have reduced proprioception through their lower leg due to a severe injury and are in a stage of rehabilitation where muscle activity without large degrees of movement is desired.

But, for healthy hockey players without injury, there’s not much to gain here which is why I hardly program it even in the most applicable part of the periodization year (immediately post-season).

Both of these bridges are “balanced”, but which one do you think is more stable and is able to absorb and redirect forces more effectively?

Future Direction For Advanced Hockey Training Program Design

The above information can be utilized to create a real hockey specific training program that’s rooted within the sports science literature to get you the best possible results.

But if you want a complete “done for you” solution, the all-new Off-Season Domination and Youth Off-Season Hockey Training programs were designed to take all of the guesswork out of it for you so you can take your game to the next level.

These complete hockey training systems include all six phases of an elite hockey training program that you can perform at any local gym (and even comes with an entire bodyweight-only version for the days you can’t make it so you never run into any plateaus no matter what life throws at you).

Remember, if your hockey performance isn’t great right now, it’s not your fault.

Real progress comes from real hockey specific training and this type of programming only comes from a hockey performance specialist.

You can’t find hockey-specific results in a non-hockey-specific program, and yet you see so many athletes these days making many of the fundamental mistakes I went through in today’s article.

Most hockey players just “exercise”, yet, after going through this information you can start to see how “exercising” makes up a very small portion of what true training you should be doing.

The days of guessing and hoping you will be a better hockey player are over – get instant access to the off-season programs here so you can leave fans, coaches and scouts jaws on the floor with how much progress you have made in a single off-season.

Final Thoughts

I covered a lot in today’s article because it’s my mission in life to contribute valuable work to the hockey strength and conditioning industry.

My work is never going to be another “me too” publication.

It’s very easy to go with what’s currently popular and marketable, and it’s very difficult to go against the trend and stand up for what you think is truly right.

I know with this article that I will be on the right side of history because we have come way too far in the advancement of sports science to suggest otherwise.

There is a big difference between marketing and science.

Beware of the business owner who knows more about marketing new gadgets than producing real hockey-specific results because although they may sound convincing, overusing this type of training methodology loses the cost-benefit analysis ten times out of ten.

If you want a real program that you can trust is built to transform you into an elite hockey player no matter what tools you have access to, check out the new off-season hockey training programs and let’s get started today.

Or, if you’re a coach and you want to learn how to create real hockey training programs that you can trust are rooted within sports science, check out the Hockey Training Specialist course so you can become the go-to coach who gets the best results in your area.

Partially true, but at the same time not at all. Balance boards are a wonderful cross-training tool. If you cherry pick a set of circumstances at aren’t the most beneficial in the application of an Indo or some other type of balance boards, then yes, the results aren’t optimal. However, the benefits, both mental and physical, of a balance trainer absolutely cannot be denied. Anyone who says as much is disingenuous at the very least. Also, I have never heard a trainer say balance board use is a quality substitute for any full motion weight training.

Hey Blayne, I think the point Dan was trying to get across was that we all only have so much time to train and there are much better exercises to use than squatting on a bosu ball.

So a balance board may not help in overall strength or speed but do you not agree that it can help with stick handling . It takes you out of that comfort zone like when your being pushed or pressured off the puck. I do believe there is a place for it. Please give me your opinion. Thanks

Hey Dan, for stickhandling I think it can be used more as a fun tool to implement for kids. If we’re looking at only skill development you are better off just stickhandling on a stable surface.

I admittedly was using some of these balance tools a year ago when I was just learning to skate and I was still randomly falling while standing on the ice and do think at that point it helped. Since finding HockeyTraining.com and starting a true hockey program I see how the exercises Coach Dan chooses to create his programs are definitely more effective and my skating has certainly improved way more that it would have had I stuck to what I was doing before. I love the scientific, and well researched approach to training. Thanks coaches!